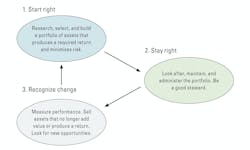

A colleague and I were talking recently about the way we view and manage our personal investments. We have both been able to save some money, and we both do everything to carefully manage it. We discovered that we followed a three-step process much like the one in the diagram nearby.

First, we understood that our savings would not produce any return if the money spends most of its time in a shoe box under the bed. The first thing to do, then, is to research and build a carefully selected portfolio of assets that produces a required return and minimizes the risks inherent in the market. We must take some risks, and our money has to work for us.

Read more asset management content in our Executive Institute.

Second, we agreed that our investment portfolio must be looked after, maintained, and administered to ensure that it is performing as required. We know that the economy is constantly changing and that we must remain vigilant for both threats and opportunities. This means we must collect data, measure performance, and identify any existing investments that are not performing well.

Third, we recognized the importance of selling underperforming assets to make sure that our portfolio stays young, vibrant, and full of potential. We know that it is often difficult to sell investments we have kept for years in the hope that that “they will recover,” but we understood that we must look forward and be in a position to maximize the future.

We sketched our three-step process on a napkin and congratulated ourselves on what we had done to better understand a complex but critically important process.

My colleague pushed the napkin over to me and said, “It is a little like managing a fleet of construction equipment.”

Indeed it is. Let’s use the diagram above and our conversation to identify three critical steps in fleet management.

Three critical steps in fleet management

1) Start right by assembling a portfolio of assets that will support operations, produce required returns, and reduce risk. We must have the right equipment in the right place at the right time, and we must build a portfolio that can handle the risks we experience when the industry changes and markets go up and down.

To select the right assets, we must look carefully at the technical specifications of the equipment we bring into our portfolio. Does it have the required size and capacity? Is it versatile and easy to use; can we maintain it as required? Does it fit our goals for standardization; what about manufacturer and dealer support and is it in line with our policies regarding environmental stewardship?

All these things—and certainly not least, the initial price—mean that our sourcing and procurement decisions must be right. If we do not start right, the path forward is going to be extremely difficult.

Read also: 10 Ways to Integrate AI into the Specification Process

The way we finance a machine is another critical “start right” decision. The market goes up and down, work volumes vary, and success at the bid table is not a given. This means that we must look carefully into financing decisions and must produce a balanced portfolio of investments able to handle peaks and valleys in the market. Long-term right-to-use lease agreements are in order for machines that will be needed for the long term. Short-term rentals and short-term right-to-use lease agreements are more suited to machines that satisfy peak requirements. The way the financial aspects are structured for the equipment portfolio in the “start right” step is critical to reducing risk and improving performance.

2) Stay right by acquiring the right equipment for the portfolio, maximizing returns, and minimizing risk. Equipment is going to work hard, however, and everything from the frame to the hydraulic pump is going to age. A four-year-old excavator may be the same size, weight, and color as it was when it was new, but it is definitely no longer the same machine: It no longer has the set of 0-hour components that it had when it rolled out of the factory.

Machines are used up; they experience wear out failure; and they need to be maintained, repaired, and rebuilt. This occurs in the “stay right” step; this is where day-to-day equipment operations come to the fore.

Preventive maintenance is the first line of defense: We need to perform all the required check, change, and adjust actions on time and to the required standards. We also must have an effective condition-based maintenance program where inspections, oil analysis, and other maintenance technologies are used to identify problems in advance so that corrective action can be taken before failure.

Maintenance programs are designed to eliminate on-shift failures, but few, if any, will be 100% effective. A good repair and rebuild program allows for a clear distinction between a repair—find the reason and eliminate the problem—and a quick fix—do the minimum to return the machine to work and sow the seeds of the next down event.

Read also: Defer Machine Replacement, but Don't Deny It

The “stay right” step is also when we spend money, generate the data needed to measure success, and perform all the administrative tasks. Costs must be recorded and coded, and key performance statistics such as hours worked, fuel consumption, and unplanned down events must be recorded routinely and accurately.

The “start right” step brings the assets into the business and builds the portfolio. The “stay right” step demonstrates stewardship of these assets and enables them to produce the required return.

3) Recognize change in the equipment fleet. Change comes from two factors: the volume and nature of the work, and machines aging and being used up in the production of work.

Recognizing change in the volume and nature of the work we do and making sure that the equipment portfolio is capable of meeting current demands is more difficult than it appears. Many machines—especially the critical specialized units—are only required for a short time. We must have the wisdom and flexibility to bring them into our portfolio for a short time, use them as needed, and return them.

Even versatile production units such as haul trucks can pose problems when volumes, haul distances, and other aspects of the work change. Own the core fleet on low-cost, long-term right-to-use agreements, but “own for the valleys and rent for the peaks.” Idle assets do not add value: A machine only has a place in the portfolio when it is working and producing a return.

The change brought about as machines are used up in the production of work needs to be adequately acknowledged. Machines age and become increasingly more expensive to maintain and repair, but many fleets try to hang on to them to the end. We need to recognize that the fleet is older tonight than it was this morning. We must recognize that machines experience wear-out failure and must have a rational way to replace assets in the portfolio when they no longer add value.

Every time we dispose of an old machine, we have an opportunity to resize and reconfigure portfolio. We also have the opportunity to introduce new technology, improve safety, and reduce environmental impact.

Read also: Six Steps to Create an Asset Structure

The demands on the portfolio change and the portfolio itself changes with regards to age, cost, and performance. Recognizing these changes, not falling behind, and seeking new opportunities puts us in a position to again start right.

How to measure portfolio success

In the “start right” step, we have the right equipment in the right place at the right time and build a portfolio of assets that minimizes risk and produces a return. Only one metric measures success: utilization. Equipment that is not suited to the work or is in the wrong place at the wrong time will not be used and will not produce a return. We will experience all the risks associated with fixed cost recovery. Without utilization, we experience the owning cost of the machine, but we do not generate any income.

In the “stay right” step, the machine is working. We look after it, maintain it, and repair it as needed. Utilization measures how we generate returns; reliability provides a baseline for success in the “stay right” phase. Reliability measures the frequency with which a machine goes down and disrupts carefully planned construction operations. All “stay right” maintenance activities are designed to reduce down events. Bad reliability is a straightforward indicator of bad maintenance. When a machine goes down, we do not generate any income and we have to spend on parts and labor.

The critical metric in the “recognize change” step is age. Reliability will go down as the old machine wears out despite all efforts at maintenance and repair. Utilization will go down because no one will want an unreliable machine that constantly disrupts planned construction operations. Owning costs go up because of low utilization; operating costs go up because of frequent down events. Tracking machine age and recognizing change in reliability, utilization, and cost will indicate when a machine is no longer adding value or producing a return.

That is the time to resize or reconfigure the fleet and again “start right.”

About the Author

Mike Vorster

Mike Vorster is the David H. Burrows Professor Emeritus of Construction Engineering at Virginia Tech and is the author of “Construction Equipment Economics,” a handbook on the management of construction equipment fleets. Mike serves as a consultant in the area of fleet management and organizational development, and his column has been recognized for editorial excellence by the American Society of Business Publication Editors.

Read Mike’s asset management articles.