How to apply the Bradford Factor to equipment downtime

For most heavy-equipment contractors, achieving effective fieldwork hinges on just two essential elements: equipment and personnel. These two components share an interdependent relationship, with equipment relying on skilled operators to fulfill their functions, and people depending on the equipment to efficiently complete their tasks. If either of these elements is missing, no work in the field will be done.

In the realm of equipment management, metrics such as downtime, mean distance between failures, and availability are used in attempts to make sure the equipment is available, ready, and capable of working. One issue that arises with these metrics is that they tend to be one-sided and do not consider the impact on the end-user (operations, clients, customers) or the organization as a whole when breakdowns and downtime occur. Consequently, department leaders tend to debate facts and exchange emotions, then resort to introducing more metrics (utilization, return on investment, etc.) in an attempt to capture a more comprehensive picture.

Be sure to check out more asset management content at The Executive Institute.

What if there were an alternative that would not further complicate business operations? What if a proven metric, extensively researched and documented elsewhere, could accurately pinpoint underperforming machinery in a manner agreeable to both maintenance and operations teams?

One such metric has been developed in the world of human resources.

Diagnosing the reasons behind employee absence is not as straightforward as machine diagnostics. There are many reasons that employees can be excusably absent, so our HR peers have created metrics that quantify the impact of absenteeism on an organization in different ways. One such metric is called the Bradford Factor, which offers a method to quantify the impact of frequent short-term absences on an organization. The underlying concept is rooted in the notion that recurrent, brief absences can disrupt a business more severely than longer, continuous absences.

The Bradford Factor formula considers the number of instances of absence and the total number of days absent. It assigns a score to each employee based on these factors. The formula looks like this: B = S2 x D, where B represents the Bradford Factor score, S is the number of separate instances by an employee within a specified period, and D is the total number of days absent by the employee within the same specified period.

Read also: The cost of downtime

The score helps HR professionals identify patterns of absenteeism and prioritize interventions. Generally, higher Bradford Factor scores indicate more disruptive patterns of absence.

This metric appears to be a valuable tool for methodically identifying underperformers that have directly impacted the business, and it can be adapted for equipment management.

First, let’s define what “S” and “D” are to isolate comparable data from the equipment management world. If S is the number of separate instances an employee was absent within a specified period of time, one can infer this to be the number of down events for equipment. If D is the total number of days absent over a specified period of time, this would be the total number of down days.

Below are three scenarios that test these data points and better illustrate what a Good or Bad score would look like:

- Equipment A was down once for a total of 10 days over a 52-week period. The Bradford Factor would be 10: (1 x 1) x 10.

- Equipment B was down twice for five days at a time over a 52-week period. The Bradford Factor would be 40: (2 x 2) x 10.

- Equipment C was down 10 times for one day each time over a 52-week period. The Bradford Factor would be 1,000: (10 x 10) x 10.

In these three scenarios, the equipment was down for the same length of time, however, the shorter, more frequent down events generated a higher score. This higher score suggests that the down event frequency would have a more negative impact on the organization.

Most down events occur on project sites where your company is relying on the equipment to perform its intended function, such as moving dirt. When the equipment is down, there are production impacts, schedule delays, and inefficiencies that equate to increased costs with lowered profitability and downstream impacts to return on investment.

How to apply the Bradford Factor to equipment management

Let’s apply this formula to a sample data set.

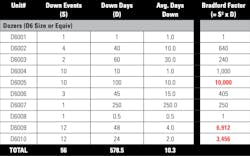

The table below lists 10 dozers and the number of down events (S) as well as the number of down days (D) for each unit. The average days down as well as the Bradford Factor are calculated and placed in the columns to the right.

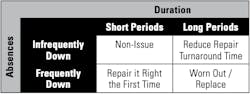

Unit D6007 had the highest number of down days and the highest average days down. Meanwhile, Unit D6003 had the second-highest average days down, yet neither Unit D6007 nor D6003 are in the top five of the Bradford Factor. How can that be? Both units had infrequent and longer-term down periods, so their Bradford Factors were much lower than units that had more frequent and shorter down events. Although both of these units certainly have issues that need to be addressed, the results suggest that it was easier for the business to plan around the downtime of these two units.

Units D6005, D6009, and D6010 have the highest Bradford Factor scores, yet their average down days are some of the lowest in the group. The magnitude of the scores suggest that it was harder for the business to plan around the downtime of these units. When the Bradford Factor is employed, you can be absent frequently but not for long periods, and you can be absent for long periods but not frequently. A machine can be down frequently but not for long periods, or a machine can be down for long periods but not frequently.

The idea of using the Bradford Factor in equipment management came up in a seminar taught by Mike Vorster for a company in Canada. The company used it to review the performance of machines on a regular basis and to identify “lemons” that needed extra attention. They used more readily available data: S was the number of repair work orders opened against the machine in the past six months; D was the number of mechanic hours spent on those work orders. The company compared the Bradford Factor values they obtained with the opinions expressed by folk who worked with the machines on a daily basis. There was an almost exact match.

In looking beyond our equipment management world, we found a quantitative way to identify the lemons in our fleet that matches what our instincts tell us about their performance.

As organizations strive for enhanced operational excellence, the Bradford Factor offers a concise yet powerful means to identify underperforming equipment and is a simple yet effective solution to improve the decision-making of maintenance professionals.

About the Author

Craig Gramlich

Craig has extensive experience in equipment management across transportation, heavy lifting, civil projects, mining, and construction sectors. Driven by a passion for cost and data analysis, he excels in enhancing equipment accounting, rate modeling, and developing programs for rate escalation and transfer pricing.

Through Lonewolf Consulting, Craig effectively unites Equipment, Operations, and Accounting departments, leveraging his extensive field experience to help companies streamline operations and find cost savings, significantly boosting ROI.

He holds a Bachelor of Commerce from the University of Alberta and a Certified Equipment Manager (CEM) certification, along with a variety of professional development courses, showcasing his commitment to ongoing professional growth.