The correct level of detail in budgeting and cost management is critical for success. If you have too much detail, you will not be able to see the forest for the trees; major problems will hide behind the sheer volume of information produced. If you have too little, you may not have the depth of information required to analyze the situation and take appropriate action.

For more asset management, visit Construction Equipment Institute.

The problem is particularly complex because many individuals throughout the organization require actionable information to support the decisions they make. Service technicians need to know how much has been spent on engine rebuilds, the CFO needs to know the cost of finance to make complex lease-versus-buy decisions, and estimators need good reliable rates for use in the bidding process.

What drives budgeting decisions?

One critical fact drives all decisions regarding the level of detail in budgeting and cost management: If you want to manage cost at a given level of detail, then you must be able to calculate both cost and revenue at that same level of detail or finer. Information can be summarized to a higher level, but it cannot be broken down to a finer level if and when additional insights are required.

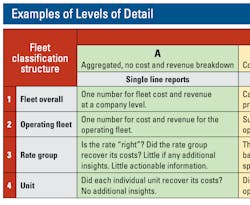

Two dimensions define the level of detail at which equipment cost information can be produced: the fleet classification structure used to group individual units into defined rate groups, operating fleets, and regional fleets; and the cost and revenue breakdown structure used to code and summarize equipment costs and revenues into a number of manageable cost types.

The fleet classification structure is most frequently based on a well-designed fleet numbering system. Information is collected at a unit level and rolled up or subtotaled by rate group, operating fleet, and the fleet overall (see rows 1 to 4 of the nearby table).

Unit-level information is, of course, critically important as you must know what it costs to own and operate each and every unit in the fleet. The detail can, however, be daunting. Most companies combine units into clearly defined rate groups to summarize and stabilize the huge amount of detail available at a unit level. Rate groups share a given rate and create a “family” of similar machines. Each group works to balance its books and provide the stable benchmark information needed to set rates, manage average age, and plan replacements. The fact that each group shares a common rate makes it possible for estimators to bid work without needing to know which particular machine will be sent to accomplish the work.

Fleet-performance metrics are often rolled up or subtotaled at an operating fleet or regional level. This makes it possible to know whether or not the on-highway fleet is covering its costs or whether it is being subsidized by the heavy-grading fleet. Summarizing costs and revenues at a regional level helps determine whether the West Texas regional fleet is performing as expected.

The cost and revenue breakdown structure is the second essential tool required to cut through all the detail and produce actionable information. The table gives an example of a three-tier breakdown structure that stretches from a single aggregated value for costs and revenue with no breakdown (column A) to a fine level of detail based on detail cost codes (column C).

The most important thing to realize is that little is achieved if costs are broken down to a fine level of detail but revenue is left as a single aggregated value. It is no good knowing how much you spent on fuel if you do not analyze revenue in a way that tells you how much you should have spent on fuel.

How to code and record equipment costs

Most companies code and record costs at a fine level of detail as a normal part of the accounting and payroll systems. Few companies, however, do this for revenue. This forces the equipment manager to work in column A, where single-line cost reports show how much was spent and earned in a given period. This is good to know, but single-line cost reports give no additional insights. They do not give the information required to analyze budget variances and determine if problems lie on the owning side of the equipment account and require action to improve utilization, lie on the operating side of the equipment account and are caused by overspending on operating cost categories, or are due to an increase in the price of fuel or due to overspending on indirect cost codes.

Reducing the level of detail to cell A1 and balancing the equipment account using one aggregated number for fleet cost and fleet revenue is not difficult. Money is spent on many machines, and many machines are charged to many jobs in an ongoing effort to recover the total cost of the fleet. If there are enough transactions, then experience, a modicum of good management, and luck will ensure that—on the average—the average will be average and the account will balance. It will, however, be nearly impossible to take appropriate action based on a single value for the gain or loss on the equipment account. There are just too many variables at play. Substantially more detail is required to analyze the situation and take the right action based on the right facts. When costs exceed revenue, the equipment account is seen as a “black hole” or an “abyss”: Everyone agonizes over it, but no one knows exactly what to do about it.

It is also difficult to take action with too much detail, such as recording the cost of every nut, bolt, and washer on every tractor or water pump. Managing cost—as opposed to simply recording cost—at this level of detail requires that revenue be broken down at a similar level of detail. The multiline cost reports (column C), where cost and revenue are broken down into many different codes, are seldom practical to produce or use.

How to use cost data to manage construction equipment

How, then, do we produce actionable information without drowning in detail? The solution lies in a careful definition of four to six principal cost types and then:

- Summarizing or aggregating detail cost codes in a way that matches the principal cost types.

- Breaking down or splitting the revenue earned by a machine to create revenue budgets that match the principal cost types.

- Producing cost reports that show actual versus budget for each principal cost type at a unit, rate group, and, at least, operating fleet level.

The principal cost types should aggregate owning costs, operating costs, fuel, and indirect costs. They should put you in a position to know where and why budget variances have occurred.

A knowledge of cost and revenue broken down by principal cost type for each rate group in the fleet (cell B3) is the starting point for budgeting and cost management. Each rate class must balance its books, and performance metrics for the rate class—especially if it is large and stable—provide benchmarks against which to make decisions regarding individual units in the rate class.

Knowing budget variances by principal cost type (column B) provides insights needed to evaluate alternative fleet-ownership strategies and take corrective action. Summarizing results at a regional fleet, rate group, and unit level produces the information required to analyze fleet performance and identify areas for action. Gains or losses in the equipment account need no longer be a mystery.

Analyzing costs and revenues by detail cost code (column C) provides additional detail when setting or calibrating rates or taking corrective action at a unit or rate group level. This is the province of specialists in cost analysis. The detail can become overwhelming or meaningless when consolidated at a regional or company level.

The question of detail is more complex than it seems. Deciding correctly is a prerequisite to providing the actionable information required for budgeting and cost management.

About the Author

Mike Vorster

Mike Vorster is the David H. Burrows Professor Emeritus of Construction Engineering at Virginia Tech and is the author of “Construction Equipment Economics,” a handbook on the management of construction equipment fleets. Mike serves as a consultant in the area of fleet management and organizational development, and his column has been recognized for editorial excellence by the American Society of Business Publication Editors.

Read Mike’s asset management articles.