We have discussed the advantages of centralizing the fleet and placing all of the organization’s equipment assets under the direct control of a knowledgeable and experienced equipment manager. The concept works, and many companies have significantly improved equipment operations by creating what is essentially an in-house rental house.

Leadership in the equipment division represents the company in all things equipment, centralizes expertise and information, and establishes standards. The centralized group is also able to move equipment freely and quickly between jobs in order to maximize utilization. The centralized group sets internal rates and establishes an internal charge-out mechanism to charge jobs for the equipment they use and credit the company equipment account.

These are three significant advantages to a centralized equipment management organization that works well. When this is not the case, the problem frequently lies in the internal rates and the internal charge-out mechanism. These can never be perfect, and different opinions exist when it comes to determining exactly how much to charge jobs for the equipment they use.

Accountability is also an issue when centralized management is not working. Jobs see themselves as accountable for the internal equipment charges and frequently have little commitment to the true cost of the equipment. They do everything they can to reduce charges to the lowest level possible within the scope of company policy and, sometimes, beyond. Job margins are calculated based on these charges, and they thus become an important part of the mechanism used to reward and recognize superintendents and project managers.

View a video on organizational structure here.

Division, area, or regional results are based on an aggregation of individual job results, and thus not even the regional manager is accountable for true equipment cost. The final reconciliation between equipment charges and true equipment costs only happens at the total-company level when results from construction operations and from equipment operations are finally consolidated into a single company-level profit and loss statement. By that time, the project manager, superintendent, or operator who is accountable for the true cost of equipment is long lost in time and space.

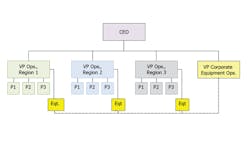

The diagram above shows an organizational chart that can be successfully used to overcome many of the negative impacts of a single centralized structure. We see that our model company has three operating regions each headed by a VP of operations and each running three projects. Each region is responsible for its own regionalized equipment fleet, and this fleet reports directly to and is consolidated into the results produced by each region. A VP of corporate equipment operations has “dotted line” oversight responsibility for the management of the three regionalized fleets.

3 advantages of equipment centralization

The VP of corporate equipment operations represents the company in all things equipment, centralizes expertise and information, and establishes standards. In our example, they manage by influence through a dotted-line relationship rather than by direct authority. This makes it more difficult and probably requires a different set of skills. Advances in computing make it possible to share information and communicate more effectively. The company still has a single point of contact and a champion for all things equipment.

Using a centralized group to move equipment across all construction operations to maximize utilization is advantageous only if the company has a relatively small footprint and if machines move frequently. It is not a significant advantage if the company works across a large geographical area, if jobs are relatively large, and if the fleet is split along business lines.

The advantage of having a centralized equipment group set internal rates and establish an internal charge-out mechanism diminishes as the company grows, as jobs vary more and more in type or location, and as the centralized equipment group becomes more remote from the field operations. Standardized rates are probably not a good thing for a company that works in Vermont and Virginia. A standardized charge-out mechanism is probably not appropriate for both production grading and seasonal maintenance. Setting appropriate rates and establishing charge-out mechanisms suited to each operating region is clearly a matter of agreement between the regional VP of operations and the VP of corporate equipment operations.

The most significant advantage of a regionalized equipment structure comes in the area of improved accountability. If a project manager says, “I am not going to return this machine, I’ve got to pay for it any way,” then the regional VP of operations to whom he reports will say, “It is our machine, we need the utilization to recover our fixed cost of ownership. Return it so that I can sell it or redeploy it.”

The key advantage is that the final reconciliation between equipment charges and true equipment costs happens at a lower level, and that the regional VP of operations can act to remedy the situation and improve the region’s performance. We have moved from “them and us” to “you and me.”

This also renders moot many of the highly emotional discussions about the rate and the internal charge-out mechanism. If project managers believe a rate is too high or if they do not like the process by which unrecovered fixed costs arising from lack of utilization are charged to their jobs, then it is a matter to be solved within their operating division with the guidance and advice of the VP of corporate equipment operations. Actual costs will lie where they fall, and regional performance will be measured as the difference between money earned and the true cost of earning that money. Internal charges are eliminated at a regional level. The games with utilization, rates, and under-reported hours stop right there.

In practice, two levels of regionalization exist. A “hard” regionalization is when operating regions are separate companies and they own and operate the equipment that supports their operations. A gain or loss statement on the equipment account is produced in the normal course of business, and this is consolidated with the gain or loss statement for construction operations to produce the company profit and loss statement. Equipment transfers between companies occur seldom and are treated as buy/sell events.

A “soft” regionalization of the fleet occurs when regions are defined by geography or business line and when gain or loss statements for the equipment in a given region are produced as subtotals within the company equipment account. These equipment gain or loss statements are consolidated with the gain or loss statements from construction operations to give a true profit and loss statement for the region. Equipment transfers between regions occur seldom and are handled by coding the unit to the appropriate region.

It seems trite, but it makes a lot of sense to align the organization and reporting structure used for equipment operations with that used for construction operations and cause the regional VP of operations to be responsible for all operations. But, you must do it under the guidance of a VP of corporate equipment operations who represents the company in all things equipment, centralizes expertise and information, and establishes standards. If not, you are headed for chaos and duplication.

For more asset management, visit ConstructionEquipment.com/Institute.