Mesh long- and short-term views for excellence in equipment management

All this excitement, change, and turbulence comes about because construction companies continuously bid for, build, and complete unique projects: discrete well-defined pieces of work each with a clear beginning and a clear end. The work is done and the projects are built by specially designed short-term project teams who have been told to “get in, get it done, and get out.” Time is always critical, and the short-term teams are clearly and specifically focused on the completion of “their” project: safely, to the required quality, on time, and on budget.

The management of the project is also clearly focused on project goals. The project has a clear scope, budget, and schedule. The team knows what they are going to build, how much it is going to cost, and when it will be done. Project plans are single-use plans. No project will ever have the same budget and the same schedule. Best practices and retained learning define what must be done, but nothing is routine. The budget is only used once, and the schedule is only used once.

There is, of course, a need to balance the constant change brought about by a focus on projects with the stability and routine required for long-term success. The company must know where it is going and how it will get there. This is where the departments come in. These are long-term teams with standing plans, policies, and procedures that change little over time. The accounting department runs in a systematic, routine manner year after year. It brings stability, enforces standards, consolidates results, and looks beyond the short-term ups and downs of individual projects. The personnel department does much the same. It brings stability, balance, and uniformity to the personnel function and makes sure that everything functions as it should regardless of the fact that most employees work on many projects in a given year.

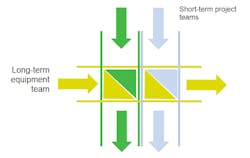

Every construction company looks for synergy and cooperation between the short-term project teams that build the work and the long-term department-based teams that implement policies and procedures and bring stability to what could easily become unmanageable chaos.

Where and how does equipment fit into all of this? What can we learn by understanding the complex yet important balance that must be maintained between projects and the equipment department?

Let’s look at it from the project’s point of view first.

Short-term project teams really do not care where the equipment comes from. They care that it arrives on their job on time and that it is able to do their job safely, reliably, efficiently, and productively once it gets there. It can be new or used, rented, leased, or owned. It must be available on their site for as long as required, and they are not concerned about where it is going to go when it leaves their job. From the project’s point of view, the costs for the machine while it is on their job must be kept to an absolute minimum, and they see no reason to pay for the machine if it is not used. Short-term project teams believe the company is best served by completing their project safely, to the required quality, on time, and on budget. They believe that equipment is nothing more than a means to this end.

The long-term team in the equipment department see things differently. They are responsible for the full lifecycle of the machine regardless of the projects on which it works. They take long-term repair/rebuild/replace decisions and establish policies and procedures for scheduled and condition-based maintenance. They know that equipment is a long-term investment and do all they can to minimize the full economic lifecycle cost. The long-term equipment team believes it is not about any one project. They believe they serve the company by managing and maintaining the equipment as an asset required to build all projects—this year, next year, and well into the future. They are the custodians of the assets, not the users.

The diagram illustrates the intersection between short-term project teams and the long-term equipment team. The short-term project teams are shown vertically because they form the core of the company and provide it with its capability to build work and earn money. The long-term equipment team is shown horizontally because it serves all projects and binds the company together.

We have seen, and it is completely understandable, that short-term project teams and the long-term equipment team have different points of view when it comes to equipment and how best to serve the company. The question now arises: Who is in charge? How does it work, and how do we maintain a balance?

The first step is to understand and respect the different points of view. Project teams must understand that theirs is not the only job the company will build. They must understand that equipment is a long-term asset and that, yes, it will need to go to another job when they have used it as needed on their job. They must understand that equipment is both robust and fragile. It can move mountains, but it can also fall victim to the smallest amount of dust or dirt in the hydraulic oil. Long-term equipment teams must understand that projects must be built safely, on time, and on budget and that the equipment is there to make this possible. Maintenance, repair, and rebuild policies must support corporate objectives. Equipment is not an end in itself.

The first thing, then, is to realize that the squares at the intersection of the project columns and the equipment row represent both challenge and opportunity. The challenge is in building understanding of the other person’s point of view. The opportunity is in building synergy and alignment where both parties work in the best interests of the company as a whole.

One of the ways to do this is to ensure that short-term teams take and are responsible for short-term decisions while long-term teams take and are responsible for long-term decisions. This is not as simple as it sounds.

Fuel is a good example. The need to fuel machines is a short-term decision. When, where, and how to do this should be the prerogative of the project team. Fuel cost is experienced on an hourly basis, and there is no reason why fuel cannot be a direct job charge. Why not handle fuel the same way as you handle cement or rebar? It all makes sense and seems simple until you realize that most engine failures start in the fuel tank and that the quality and cleanliness of fuel is critical to the long-term life of every machine in your fleet. So, while fueling—when and where—may be a job responsibility, there is no doubt that fuel—buying it, storing it, accounting for it, and ensuring that it meets cleanliness standards—is most surely a long-term decision. The work will be done to-day, the benefits will be realized well in the future.

Ground engaging tools, tires, and tracks are much like fuel on long-term jobs where the project team can and should experience the true cost of the operating decisions they make and the actual conditions under which the machines work.

Another opportunity to build synergy and alignment comes in the design of job-level incentive and recognition programs. Job margin is critically important, but it cannot be the only metric used to incentivize short-term project teams. The true cost of the equipment and the impact of project decisions on the lifecycle cost of owning and operating equipment must be factored into the process one way or the other. Similarly, there must be a way to recognize the contributions made to project success by the long-term team that serves as the custodian of the equipment asset and works to ensure that safe, reliable, and productive equipment is available as needed on all jobs across the company as a whole.

As with everything, it is a matter of compromise and balance. Short-term project teams bring excitement, change, and flexibility. They build the work and earn the money. Long-term teams look after our resources and our assets and give us the capability to perform at exceptional levels. There must be a balance between long-term teams and short-term teams.

Companies that do it well flourish. Companies that do it badly constantly struggle with internal conflict, misalignment, and waste.