Recently, someone said to me, “Mike, enough policy and philosophy, what would you do if you were responsible for implementing the material we have spoken about during the past four days. No fancy ideas, just hard realities?”

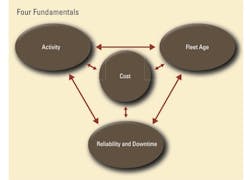

Policy and philosophy are good, but what are the fundamentals and how do you implement them? I have been thinking about equipment management for close to half a century; I suppose I should have an answer.

Here are the four steps I would take.

1) I would know my cost.

Knowing your cost is the price of admission to the construction industry. When it comes to equipment, you absolutely must know the hourly (or daily) owning and operating cost of each unit and each class of equipment.

Why: You need to know the hourly owning and operating cost of the equipment in your fleet in order to manage your operations and provide reliable estimates of equipment cost when bidding for future work. You may be able to manage your fleet reasonably well without a good knowledge of cost. You certainly cannot produce reliable bids for future work unless you are confident that you know what it will cost to own and operate the equipment you will use.

How: You need five things: (i) a good costing system for recording actual costs, (ii) a logical cost-coding system to code actual costs by principal cost type (owning and operating) and sub-types (depreciation, taxes, parts and labor), (iii) a logically numbered fleet so that you can assign costs to units and roll unit costs up into rate classes, (iv) an hourly (or daily) budgeted rate for each class and category with sub-rates that correspond to the cost codes used to record actual costs, and (v) a reliable system for recording hours (or days) worked to calculate actual cost per hour or day.

Calculations: You use the sub-rates and the recorded hours (or days) worked to calculate earned value budgets for each cost type, individual unit, and rate class. You compare these budgets with the actual costs experienced, calculate variances, understand the causes of the variances, and take needed action.

2) I would measure and manage reliability and downtime.

Reliability and downtime provide a true measure for success in maintenance, repair and rebuild operations. They are two different things. Reliability measures the frequency with which a machine goes down; downtime measures the duration. Frequent breakdowns are a good leading indicator for major breakdowns.

Why: If you do not measure and manage reliability and downtime then you have no way to measure the effectiveness of all the money you spend on repair parts and labor, maintenance, and condition assessment. Money spent is an input; reliability and downtime are outputs. You cannot evaluate the wisdom of providing inputs if you do not measure outputs.

How: You have to know how frequently a machine goes down on shift. This is easily done by using the work order type codes described in “Reliability and Downtime” (January 2016). You also need to measure downtime. This is difficult as downtime seems to be something no one wants to talk about or record. The work order process set out in the above article solves the problem and makes it possible to distinguish between repair downtime and scheduled downtime.

Calculations: The metrics are simple. For reliability, it is the number of on-shift failures per 1,000 hours worked; and for downtime, it is the number of repair or scheduled down hours per hour worked. Without these metrics, you absolutely will not know how effective your maintenance operations are and you will not know what you are “buying” with all the maintenance money you are spending.

3) I would know how active my fleet is and keep it working.

Fixed cost recovery is a major construction risk. This is especially true when it comes to the equipment account where fully one-third of the cost of owning and operating a fleet is fixed and does not change regardless of the number of hours (or days) units work in a year. Fixed cost recovery is critical, and units or rate classes with low utilization will never be cost-competitive

Why: You own or lease machines 24 hours per day, 7 days a week. Cost per hour, or cost per day, is therefore extremely sensitive to utilization; you simply cannot afford the fixed costs of idle equipment. You have to be ruthless when it comes to the deployment, availability and utilization of your fleet.

How: You have to know how much time machines spend off-site, in the yards or in storage sites. The fact that they are not on-site does not mean they have become free. Once on-site, they need to be able to work when needed and not be broken down (on-shift downtime). Lastly, and importantly, you need to know how much time machines spend working and contributing to site productivity. Take care with sensor-recorded idling time. Some idling—but certainly not all—is frequently part of the production cycle.

Calculations: Again, the metrics are simple. Deployment is the number of weeks in the past 12 months a machine has spent on-site and expected to work. Availability is the percentage of deployed time that a machine is up and running and able to support production. Utilization is the percentage of the “up and running and able to support production” time that the machine spends actually supporting production.

4) I would have a laser focus on fleet age.

Fleet age measures the fleet’s ability to do work into the future. It forms the basis for the repair/rebuild/replace decision and facilitates long-term capital expenditure plans and other acquisition decisions.

Why: The vast majority of machines wear out. When they wear out they become less productive, less reliable, and more costly. Managing the age of your fleet is therefore critical. If the fleet is too young, you will tie up too much capital and have high fixed ownership costs; if it is too old, productivity, reliability, downtime and repair costs will be real problems.

How: The first requirement is to establish and constantly calibrate the “sweet spot life” or benchmark age for each rate class and to establish early warning life zones that clearly show when machines are approaching, at, or beyond their sweet spot life. You also need a knowledge of the present age and hours worked in years past for each unit.

Calculations: The present age of each unit and a knowledge of hours worked in years past can be used to produce a reliable forecast for the time when a unit will be at or beyond its sweet spot life. Simple graphics will show how many units are likely to be candidates for replacement or rebuilding in years to come, and realistic long-term capital expenditure budgets can be developed based on reasonable assumptions of future workloads.

After close to half a century of work and study in the area, those are the tools I would put in my asset-management tool box. I would know my costs, measure reliability and downtime, know all about the activity of my fleet, and watch fleet average age like a hawk.

But, good tools do not make a good mechanic. They sure help, but it takes real skill to use the right tool in the right way to solve a problem. This is where skill and experience come in. How do you solve the cost overrun? Is it a problem with reliability or age? Are the high owning costs due to downtime, deployment or utilization? It is your call. At least you have the tools.

Knowledge is not an end in itself. Success depends on how you put it to work.