I have the opportunity to work with some great companies and learn from the best. So it is natural that I have a little storehouse of knowledge about what the best companies do when it comes to managing their fleets. I share the following in the hope that you can look at your operations and see what you can do to share the success enjoyed by many world-class construction companies.

The first lesson is that great companies do a few things very, very well. They do not try to do everything. They do what is important. They do it right, first time, every time. There are no compromises, and nothing is left to chance.

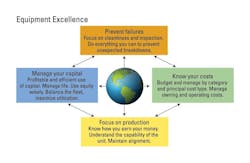

Let’s go over four critical areas.

1) Prevent failures.

Great companies do everything they can to stop their machines from breaking. They recognize that there are substantial costs associated with each and every on-shift breakdown. They know that reliability holds the key to success and achieve world-class performance in two areas: cleanliness and inspection.

Machines consume huge quantities of air and fuel, both of which contain dirt that grinds away at expensive machinery. Oil circulates thousands of times through crankcases, gears, pumps, pistons and cylinders. Dirt in oil is just grinding paste waiting to go to work, and the damage it causes never heals. Great companies do not give dirt a chance. They keep their fluids clean, filter relentlessly, and never let it wreak havoc. Their focus on cleanliness improves reliability, increases component life, and lowers cost.

Machines constantly talk to us, and inspection programs are our eyes and ears. We can either have a program that looks, listens and tells us what we need to know, or we can turn a blind eye or deaf ear and have the machine demand our attention by breaking down at an inopportune time and place. Condition assessment and a competent condition-based maintenance program massively extend the range of a conventional schedule-driven preventive maintenance program. Great companies train operators and service technicians to constantly monitor the condition of their equipment and use technologies such as oil analysis to gain additional information and detect deterioration inside sealed compartments. They act on the information they receive and rigorously schedule the work needed to get ahead of the breakdown curve and prevent failures.

2) Manage capital.

Equipment is a capital-intensive business. Managing the capital already invested and making competent long-range plans to secure capital needed to grow and flourish are essential for success. Most companies emphasize profitability and the profitable use of capital. Great companies do the same but always ask two questions: “Are we making money?” and, more important, “Are we making efficient use of the capital invested in our fleet?”

They generate the returns needed to secure capital for replacement and growth by constantly emphasizing both the profitable use of capital and the efficient use of capital. Nothing turns off investors—internal or external—as much as an equipment account that loses money or a machine that stands forlornly along the yard fence. Great managers of capital focus on three things:

First, they manage life and keep fleet average at or about the optimum. They know that capital is not used efficiently if the fleet is too new with too much capital invested in it. They know you cannot generate the profits needed to use capital profitably if the fleet is old, unproductive and expensive.

Second, they wisely use equity, their own money. Using your own money to acquire equipment has many advantages, but liquidity and working capital requirements cannot be overridden. Efficient use of equity funds can be greatly enhanced by maintaining a balanced portfolio of equity investments, loans, leases and other acquisition options.

Third, they balance the size and composition of their fleet and maximize utilization. Every replacement decision is seen as a chance to review the size and composition of the fleet and adjust to suit workloads. Great companies are not afraid to force replacement decisions if the utilization of a certain category of equipment falls below par. Low utilization is, quite simply, inefficient use of capital.

3) Know your costs.

Knowing your costs is the price of admission to construction. Knowing your equipment costs and having reliable, well-balanced rates is essential to producing the reliable competitive estimates needed to be successful. It is not enough to know that the equipment account as a whole “made money” or “lost money” in a given year, or to know that the rates, on average, for the fleet as a whole, are sufficient to recover the owning costs experienced by the fleet as a whole.

Great companies know what it costs them to own and operate each class or category of equipment in their fleet. They understand that every equipment category must look after itself and know that the rate must cover the costs experienced by that category. They do not have the dozers subsidizing the mechanics trucks and the pavers subsidizing the milling machines. They know their costs by category and do not rely on good fortune in the workload mix to balance their books.

Great companies also budget and manage costs by principal cost type and do not compensate for overruns in the fuel budget by borrowing from the repair parts and labor budget. They generate earned value budgets by principal cost type, correctly record their actual costs, understand why budget variances occur, and take appropriate action. They divide and conquer cost uncertainty by managing owning costs, operating costs, and fuel as three starkly different cost types. Owning costs are mostly fixed pre-determined annual costs where utilization holds the key to success. Operating costs are almost exactly the opposite; they are hourly costs that depend on hours worked and good day-to-day operating, maintenance, and repair decisions. Fuel costs are high-risk pass-through costs where success depends on buying wisely, storing well, and managing waste. Combining these three cost types into one budget blurs cost information to the point where it is of little value. Separating them gives the clarity needed for actionable information.

Great companies know their costs with clarity and confidence.

4) Focus on production.

Equipment managers, rightly and properly, believe the world revolves around their fleet. Yet construction companies earn their money by safely completing construction to the required standards, on time and on budget. Equipment and equipment-management decisions that run counter to this are seldom, if ever, in the best interests of the company.

Great companies know that equipment is an important means to their desired end. They know that equipment specialists understand the capability and application zones of the units they manage and that they can provide important expertise in operations, means and methods. Bad companies separate operations management from equipment management and build barriers between centers of excellence in their business. They compound the error by placing accounting and finance in its own silo and setting up a three ring circus where each ring acts with little regard for the other two. Great companies do not do this. They bring accounting, finance and equipment together in a closely aligned organization that focuses on production and on completing the work. There are no silos, no silo metrics, and no silo wars.

Great companies do a few things but do them very, very well. They:

• Prevent failures, inspect and maintain to ensure that their fleet is reliable.

• Manage their capital, focus on both the profitable as well as the efficient use of capital, constantly balance and right size their fleet to ensure that the right equipment is available.

• Know their costs by individual equipment category and cost type to develop actionable cost information and ensure that their fleet is affordable.

• Focus on production by knowing how they earn money, eliminating silos and maintaining alignment to ensure that their fleets are productive.

Can you do any less?