Few questions have concerned me more than: “I want to lower my bid, so why must I include depreciation for machines that are fully written off?” It is a tough question because it combines semi-valid short-term logic with a mindset that has dangerous long-term implications.

When faced with a tough question—always tell a story! This is a parable of two brothers who grew up on a farm that had been in the family for four or five generations. Their father worked hard to make ends meet and to make sure that everyone enjoyed a good but frugal lifestyle. The family had everything it needed, no more and no less. Life was good.

The father passed away when the brothers were in their early 30s, at which time the elder brother decided to cash out his inheritance and start a heavy grading company. The younger brother wanted to stay on the farm, so they went together to the bank to sort things out. They were astounded to hear that the farm was valued at several million dollars and pleased to hear that the bank would happily loan half the value to the younger brother so that he could give the elder brother his inheritance while he continued the farming enterprise.

For more on asset management, click here.

Life was tough for the younger brother. He now had to succeed as a farmer and make substantial payments to the bank. He scraped and pinched, sold some pieces of the farm, used his assets wisely, and slowly worked his way out from under the obligations of the loan.

Things were good for the elder brother. He was heard to boast, “I can get the work I want when and where I want it because, you see, my equipment is all paid for and I do not need to include loan payments or depreciation charges in my equipment cost calculation.”

Things went well for five or six years until the elder brother needed to replace his fleet and found he did not have the cash needed to buy the next generation. Prices had gone up and the cash that had spun out of the business had been spent on the good life associated with success. The bank was, however, delighted to help him out, so he borrowed the required funds or entered lease agreements to renew his fleet. All of a sudden, business was not as good as it had been. Yet he had to make substantial monthly loan payments regardless of rain or snow, how hard he worked, or how successful he was at the bid table.

Life seemed to have turned against him. His younger brother was about to sell a small tract of land and pay off the note on the farm while he was sitting on a pile of debt and struggling to make payments to the bank which now, effectively, owned his business.

The elder brother had, in fact, given away his inheritance by not recognizing that equipment is a depreciating asset. His fleet was worn away or consumed in the production of completed construction, and by not providing sufficiently for depreciation, he was not able to regenerate the capital needed to survive in the long run. The short-term urge to underbid the competition overcame the wisdom needed for long-term survival.

Depreciation and its role in the equipment cost calculation is a complex subject. Four important concepts help establish some clear guidelines.

1. Costs and charges.

These are two different things, and you need to use the terms with care. You experience a cost when you actually spend money that flows out of the business to another entity. Buying fuel from a supplier is clearly a cost. Charges do not entail the spending of money. They are journal entries that debit or credit accounts within the organization to make sure that the books properly reflect what is going on inside the business. When you buy a machine, it is a cost—or more correctly, a capital expenditure—because money has flowed out of the organization to acquire an asset that will last for more than one accounting period. When you depreciate a machine, it is a charge because no money changes hands. You are simply reducing the value of the asset to reflect the fact that it has been used to produce work and has experienced some, as yet unknown, loss in value. No money has left the organization. It has simply shifted from one account that keeps track of the value of the equipment owned to another account that keeps track of the depreciation charged to each unit in our fleet.

2. Book value.

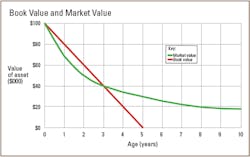

This is simply the original capitalized value minus the accumulated depreciation charged to the machine. It is a complex subject governed by accounting rules that define (i) the asset’s original cost, (ii) its estimated life, (iii) its estimated residual value, and (iv) the actual method of depreciation selected. Most companies tend to be simple and conservative in their accounting and depreciate the asset down to zero over a relatively short period using the straight-line method. The red line in the accompanying diagram shows how this is done for a $100,000 asset with an estimated life of five years.

3. Market value.

Market value is different from book value and depends entirely on what the market thinks the machine is worth if it were sold at any point in its life. Market value is a volatile moving target, but we know that (i) it decreases rapidly in the early years and much more slowly in the later years, (ii) it seldom stops going down as the machine gets older, and (iii) it seldom actually reaches zero. The general shape of the market for construction equipment is shown by the green line in our diagram. From this we can see that:

• Book value is higher than market value for the first three years, and we would be “upside down” relative to book value if we sold the machine in this period.

• Market value is higher than book value from Year 3 onward, and we would experience a gain on book value if we sold the machine at any time after Year 3.

• After Year 5 there is no more book depreciation, but the market value of the machine—the value of our asset—continues to decline.

4. Cost of capital.

If your equipment ties up money provided by a bank or financing company, they expect a return. Similarly, if your equipment ties up money provided by your owners or stockholders, they expect a return. If equipment does not generate a return on the tied up capital, then no one—banks, lending companies, owners or stockholders—will invest their money in your fleet. Your fleet will neither attract nor support the funds needed to survive, much less grow, in the future. The amount of money tied up is the market value not the book value, an imaginary value based on accounting policy.

Consider the diagram to see what happens in the period from age 2 years to age 5 years. The machine would be charged with $60,000 of depreciation, and at the end of this period it would be “fully written off.” The true cost experienced in that period is the loss in market value of $20,000 ($50,000 to $30,000) and the cost of tied up capital of 10 percent on the average value of $40,000 (the midpoint between $50,000 and $30,000). The charges, based on accounting policy, are much higher than the costs based on estimated market values.

The opposite happens in the period from 5 years to 8 years. The machine is fully depreciated from an accounting point of view, and there are no more charges. This generates the myth that the machine is “free” despite the fact that it has value and, presumably, is doing valuable work. If we keep our focus on market value and on the actual costs we are experiencing, then we get a completely different picture. The loss in market value—an undeniable cost to the company—is $10,000 ($30,000 to $20,000), and the cost of tied up capital is 10 percent on the midpoint value of $25,000. The machine is an asset from which current and future economic benefits are expected, it has lost value, and you simply cannot believe that it is free.

The eldest son quickly and easily wrote off his investment when he had the money and he saw it as free. He lived off his seed corn. He lost sight of the market value of his fleet and of the simple fact that you must, at some stage, recapitalize your fleet. If you do not have your own resources to do this, you will need to use other people’s money and that could prove to be both expensive and risky.