I frequently hear talk about comparative shop labor rates and outsourcing. A lot of it makes sense, and it certainly is important to constantly check that the services you deliver are competitive with those you can buy from dealers and other outside sources. Deciding on how much to do in-house and how much to farm out to others is not easy. Many factors come into play, making it difficult to compare apples with apples.

Let’s do two things. First, we will set up a way to better understand the numbers and take action based on hourly labor cost, and second, we will list and discuss some of the important intangibles that influence decisions regarding the need to maintain shop and yard facilities.

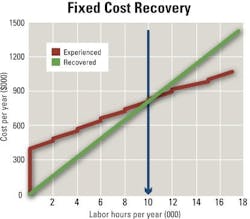

Cost comparisons are always difficult. They can’t be made on the basis of hourly costs alone, and it is critical to understand the relationship between the way you actually experience your shop costs and the way you recover those costs by producing or “selling” labor hours. The classic break-even chart below helps to understand how it works.

The red line tracks how the actual costs of running a shop-and-yard operation increase as capacity is added and the number of labor hours available to do work and support the fleet increases. It is not a straight line. A large portion of the costs are fixed, and in the example used, the red line starts at $500,000 per year because of fixed annual costs such rent, insurance, property tax, electricity, water, telephones, internet connections and all the other fixed costs of managing and maintaining the facility. These annual costs invariably come to a substantial sum and change little regardless of the number of mechanics working or labor hours produced in the shop.

The red line slopes and steps upward and outward from the initial fixed cost of $500,000 per year as the variable costs associated with producing mechanic labor hours are added to the initial fixed annual costs. Our example assumes that labor costs $32 per hour or about $67,000 for a 2,080-hour year. The example also includes a $20,000 per-year increase in fixed cost for every mechanic added except for the increase that occurs at 8,320 hours when the line moves up by an additional $60,000 per year for the additional facilities and/or supervision added at that time.

The line pushes relentlessly upward and outward as capacity grows and ends up showing that it costs close to $1,200,000 to produce and deliver 16,000 mechanic hours with eight mechanics. A lot of detail has been left out to keep the example short, but every single shop—yours or the dealer’s—has a line similar to the red line shown in the chart that compares total cost experienced vs. hours produced.

The problem—and the challenge for management—arises from the fact that costs are recovered at a constant hourly rate by charging for the work done. Recoveries are shown by the green line which, in the example, slopes at $80 per hour. This recovery rate or “labor rate” means that a total of $1,280,000 would be recovered by charging individual items of equipment, jobsites, or other cost centers a total of 16,000 mechanic labor hours at $80 per hour. At this point, recoveries exceed cost—the green line is above the red line—and both the fixed and the variable costs experienced in running the operation are recovered. The lines do, in fact cross a little below 14,000 hours—the critical and well known break-even point for the operation.

If the fleet size and activity is such that we need at least 14,000 mechanic hours per year as shown by the blue line, then the operation assumed in the example can and will make ends meet by charging $80 per hour for mechanic labor. If the hours needed drop below 14,000 and the blue line moves to the left, then things become difficult. Let’s imagine that the hours needed goes down to 10,000 for a given year and the blue line moves to 10,000. The first and most obvious thing to do is to reduce the number of mechanics working in the shop to five. That certainly helps but, at 10,000 hours, the red line is well above the green line, and the slope of the green line will have to be increased in order to make ends meet. If you do the arithmetic, you will see that the labor rate will have to go up to $94 per hour to break even. It seems unfair: You have made the hard decision to reduce mechanic labor from seven to five, you have the right number of people on the payroll, and yet, you have to increase the rate by 17 percent. Welcome to the real world of fixed-cost recovery. It seems wrong to say, “The less I do, the more I need to charge.”

Your dealers’ or suppliers’ shops exhibit exactly the same patterns, and as we know, they work hard to drum up business and sell more hours. They can even discount their rate a little because, as long as the green line slopes up more steeply than the red line, there is a contribution to fixed-cost recovery. Not so for the contractor’s shop where the object of the exercise is to use as few hours as possible to repair and maintain your fleet and ensure that your fleet costs are as low as possible. Let’s say it again: For dealers and suppliers, success is serving their customer while selling as many hours as possible. For contractors and end users, success is serving their customer and using as few hours as possible to reduce end use cost. The fewer you sell, the more difficult it is for you to recover fixed costs.

Understanding the break-even chart and knowing that the solution lies in managing fixed rather than variable costs enables you to take the right action. If, in our example, the hours needed goes down to 10,000 per year and the blue line moves to 10,000, then action must be taken to reduce fixed costs. If you do the arithmetic, you will see that you need to eliminate the additional fixed cost at 8,320 hours and reduce the overall fixed cost to $400,000 per year to have an organization that can break even when it produces 10,000 hours per year at $80 per hour.

Eliminating that amount of fixed cost in an organization that you will contend is already lean will not be easy. But it will not be easy to expect your internal customers to accept a rate increase of 17 percent. Indeed, going from $80 to $94 per hour as an internal rate may be all that is needed to drive folk away from your shop and outsource to organizations that charge less than $94 per hour. That will make it even more difficult to break even and things will get out of hand in a heartbeat.

The key lies in understanding that the shop is much more than a workshop. It is, together with the yard, the nerve center for the company’s field operations. It provides space to receive, store and make ready the barrier wall, formwork, bridge screeds and other materials that the company uses on a daily basis. It provides both the space and the resources to ensure that assets, no matter how small, are inventoried, stored and protected. It supports and provides a home base for the preventive-maintenance technicians and field mechanics who keep the fleet running, and it is not unusual to require that everything functions 24/7 so that machines can be fueled, maintained and repaired in the field outside normal work hours. The many critical support functions performed by the shop and yard are often taken for granted. They are difficult to cost and, if provided by dealers and suppliers, extremely expensive.

Decreasing the fixed costs associated with a shop and yard is not easy. You pay for the property, for utilities, insurance and other costs associated with owning the facility. You pay for maintaining and managing the shop and the yard and for providing the services needed to support construction operations. Suppliers do not provide storage for underutilized equipment, formwork and bridge screeds. They do not run a dispatch operation and dispense fuel and lubricants. You cannot compare your labor rate with theirs if you provide a broader range of services the fixed costs of which are recovered in the labor rate.

Wise companies treat the yard as a true overhead and have the shop labor rate carry only the fixed costs associated with the shop itself. This makes it possible to compare apples with apples when looking at outside rates and helps to manage the fixed costs of the shop and the yard as two different and distinct cost centers.