Job costing can be described simply as charging each job or each phase code for the resources they used to produce work, and crediting the job or job-phase code with the budgeted value of the work done.

The labor portion of a given job phase code is accurately and quickly known through the payroll system. Daily time cards are used to assign cost to the appropriate phase code. The same is true for material costs. Vendor invoices flow through the accounts payable system where phase codes and materials-received notes are used to assign material costs to the correct job and phase codes.

The equipment cost portion of job costing presents a different story. Equipment costs do not occur as uniform, steady, and known payments that can be charged to job phase codes on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis. Most occur in transactions of varying size at widely separated points in time. Therefore, equipment costs cannot be used in the job costing process until they have been collected and averaged over the life cycle of the machine. This “adding and averaging” process happens in the equipment account where the actual costs likely to be experienced throughout the lifecycle of a given machine are used to calculate a uniform cost-recovery rate that lies at the heart of a complex and invariably controversial equipment cost-recovery process.

Setting up the equipment cost-recovery process is not easy, and every company does it slightly differently. The equipment executive, however, must know the details of the system and carefully communicate it.

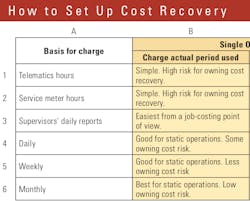

Column A gives six options for the basis for the equipment charge. Even if there is an hourly rate, we must still decide whether “hours” are defined by machine data transmitted via telematics, service meters, or supervisors’ daily reports (rows 1 to 3). Each has advantages and disadvantages.

Machine data is, or should be, “correct,” easy to collect, and easy to import. It may, however, not apply to all units. Reliability is often an issue, also. Telematics systems record the briefest definition of hours worked as idle time and short shutdowns are frequently not part of the hours-worked calculation. Service-meter hours must, in the vast majority of cases, be collected and recorded by hand. This is a significant disadvantage that is only overcome by the fact that service-meter hours must in any case be collected to drive the preventive maintenance system. Supervisors’ daily reports are a good solution if hours worked are collected routinely, honestly, and, preferably, electronically. Regardless, if hours worked is the basis for the charge, it must be defined in order to move away from the endless “hour-meter wars” we so often experience.

Rows 4 to 6 show that days, weeks, or months deployed on site can be a satisfactory basis for cost-recovery charges for certain types of assets such as variable message boards, pumps, and utility tools that are required on site but are not necessarily involved in production operations.

The next step in setting up the system is to decide whether to calculate rate-recovery charges using one rate to cover both owning and operating costs (columns B and C), or to use two separate rates: one designed to recover owning costs and one designed to recover operating costs (columns D and E). With a single rate, the option exists to require sites to record and pay for only the actual hours or days used (column B) or to pay a minimum number of hours or days per month regardless of actual usage (column C).

A single-rate system without a minimum has many advantages. Jobs pay for the machines they use for the actual hours or days they use them. The allocation of equipment cost to phase codes on an hourly or daily basis is simple, and the job-costing function works as it should. There is, however, a huge risk. The jobs pay only for hours or days used and do not carry the risk of recovering the fixed cost of owning a machine and keeping it in the fleet. Standing time and idle time are “free” at the job level, so hoarding or over-equipping jobs becomes prevalent. Waste is not measured.

Insisting that jobs pay for a minimum number of hours or days per month, moving from column B to column C, does solve the problem to some extent. The jobs pay for the minimum number of hours whether they use them or not, and the equipment department knows that the equipment account will recover a fixed number of hours or days for every month the machine is deployed to site. The risk of recovering monthly owning costs is thus passed on to the site, where it is managed by site managers who make the day-to-day operating decisions. Job-phase codes are debited with the cost of the equipment actually used to produce work as well as the cost of any associated standby or idle time. The process is simple, but it is often seen as punitive and the cost of standby time can introduce a real inaccuracy into the job-costing system.

The dual-rate approach—columns D and E—is often used to overcome the disadvantages of the minimum-cost approach (column C). Each machine has two rates and two cost-recovery mechanisms.

One is designed to recover the variable cost of operating, and the second to recover the fixed cost of owning the machine and keeping it in the fleet. The dual-rate approach is conceptually and theoretically the most correct and equitable to all concerned. But it is complicated and must be managed with care.

Two approaches are found in practice. The first uses an hourly operating rate to recover operating costs together with an hourly owning-cost rate and monthly minimum to ensure the recovery of fixed owning costs. If hours worked in a given period fall below the minimum needed to recover fixed owning costs, then a sum equal to standby time (minimum hours minus hours worked) multiplied by the owning rate is debited to a job-level standby-phase code.

It is complicated, but it works. Above all, the cost of standby equipment, a critical waste on the job, is measured by generating debits to the job-level standby-phase code.

The second approach also uses the product of an hourly operating rate and hours worked to recover operating costs, but then uses a fixed daily, weekly, or monthly rate to recover owning costs for the time the machine spends on site. The job-phase codes are charged for the operating costs, and the fixed owning costs are either allocated to phase codes or charged to a single on-site equipment owning-cost phase code. This approach is less complex and works well for substantial support equipment such as large pumps and tower cranes that stay on site and support many operations for a fixed period of time.

The equipment charge out system must be fair, reasonable, and well understood. It does, however, not need to be the same for all types of equipment. A department can and should use a simple weekly or monthly rate (B5 or B6) for as many classes and categories as possible. Use dual rates with monthly owning rates for major support equipment, and dual rates with minimums and hourly owning rates for major production equipment. Keep it fair, and communicate it well, understanding the two masters: the job costing system and equipment account cost-recovery system.

For more asset management, visit ConstructionEquipment.com/Institute.