This is the first of two articles (see Part 2) that use a complex diagram to follow the money for a typical equipment-using company. This article will focus on the relationship between the job account and the equipment account, and will look at the operating-cost side of the equipment account. The next article will develop the same diagram a step further by focusing on owning costs and the capital account.

Every company has a different flow of funds and terminology, but the concepts will be the same. Use the diagram as inspiration to produce one specific to your company. You will be surprised at how complex it becomes as you diagram the transactions involved in the management of an equipment fleet.

Let’s start at the top and see how it works.

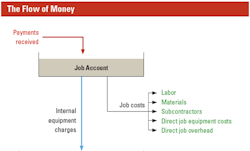

The first and most important inflow into the system comes from the payments that the company receives from completed work. Nothing functions well if receipts into the job accounts are either insufficient or not timely. It is important to maximize this inflow consistent with safety, quality, customer relations, and good business practices.

Costs that flow out from the job account are typically divided into labor, materials, subcontractors, direct job equipment costs, and direct job overhead as shown in green at the top right. Internal equipment charges also flow out of the job account.

These are shown in blue to make a clear distinction between a cost—when the funds flow out of the business as “real” or “green” money—and a charge—when one part of the organization charges another for services rendered with “internal” or “blue” money. The important distinction between direct job equipment costs (green money) and internal equipment charges (blue money) depends on what is and what is not included in the internal charge rate. Some companies include items such as ground-engaging tools, rental equipment, fuel, and field maintenance labor as direct job equipment costs and do not include them in the rate. Others include nearly everything in the internal equipment charge rate with direct job equipment costs reduced to an absolute minimum.

Internal equipment charges generate debits against the job accounts and credits to the equipment account. This is where the equipment manager’s responsibility for cost and cost management starts. This is where we look at what it takes to balance the equipment account and know what it costs to own and operate the fleet.

The first step is to ensure that the internal equipment charges that flow from the job account to the equipment account are correct. They depend on three things: the internal charge-out rates themselves, the “small print” that defines how these rates are used in calculating charges (“How to Recover Equipment Costs,” July 2018), and the reliability of the recording and reporting system. The equipment account cannot be balanced if you do not set up and faultlessly manage the process by which internal equipment charges flow from the job accounts to the equipment account.

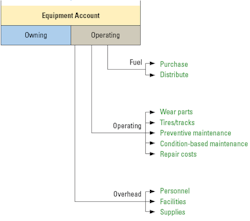

The next step in the cost-management process is to divide the equipment account and the charges that flow into it into two clear parts: the owning side of the house and the operating side of the house. This month’s diagram shows operating costs; the next article will show and discuss owning costs.

The equipment account must be managed as two separate parts because owning costs and operating costs are different. Owning-cost management is about recovering the fixed costs of ownership and making good on the commitments made; operating-cost management is about managing day-to-day expenditure on the resources needed to keep the fleet up and running.

The first thing to notice is that the operating costs are indeed costs; there is no blue money on the operating-cost side of the diagram. Expenditure is frequently divided into the three main categories shown in black with their associated subcategories shown in green. It requires skill and determination to spend wisely, eliminate waste, and manage resources efficiently.

Fuel is by far the largest subcategory. It requires special attention, and it costs a lot to receive it, store it, and distribute it to point of use. Condition-based maintenance covers all the nonscheduled, inspection-based actions taken to stop the fleet from breaking. It is a legitimate subcategory: Every dollar spent saves many in the repair cost category. Overhead, or equipment indirect cost, is an important operating cost subcategory that must be understood and managed with care. It cannot become a dumping ground for unmanaged and/or unallocated costs (“Proper Placement of Overhead,” April 2016.)

Use the diagram to ask and answer four questions:

- Do I understand the flow of funds through my organization, and can I draw a diagram like this?

- How do I define direct job equipment cost? Does everyone know and understand what is in the rate and what is not in the rate?

- Am I absolutely sure that the systems, policies, and procedures for determining the internal equipment charges are as good as they can be and that they are being implemented as required?

- Do I know how much of my operating cost dollar is spent in each of my defined operating cost subcategories? Am I spending too much on repairs and too little on maintenance?

Four yeses would be good.