Editors note: This article has been updated.

Lots of things go wrong and lots of problems become difficult to manage if you let the average age of your fleet swing wildly. If your fleet is too young, you are a slave to high fixed costs, high depreciation, and constant demands for extraordinary utilization. If your fleet is too old, you rush around all day trying to weld, patch and fix machines that have passed their “sell by” date.

Managing and maintaining fleet average age is, in my opinion, the single most important thing you can do.

Three reasons fleet average age is important

Three good reasons explain why it is critical to maintain fleet average age at or around the sweet spot: the time when owning and operating costs are reasonably in balance and the lifecycle cost per hour is at a minimum.

1) You can defer replacement, but you cannot deny replacement. Machines are used up in the production of work. Even the old lattice-boom crane or the old jaw crusher will eventually come to the end of its life. You can defer replacement, but you are living on your seed corn if you do not replace the assets that are used up in the production of work. It is not the number of machines you have; it is the number of productive hours remaining in your fleet that determines your potential for future success.

2) There is no such thing as a free lunch. If you reduce capital expenditure and fleet average age increases, then operating costs—the cost of the parts and labor you need to keep your fleet up and running—go up. There is no such thing as a free lunch. Reducing capital expenditure will save investment and capital cost, but operating expenditure and the demand for skilled field labor to repair and maintain the aging fleet will go up dramatically. Geriatric medicine is much more labor-intensive than sports medicine.

3) Beware the spiral of doom. Old and less reliable equipment is not capable of achieving the availability and productivity needed to produce work and generate profits. This, unfortunately, is exactly when you need money to replace the fleet. It becomes extremely difficult to reverse the trend and replace the equipment you need. When fleet average age goes up, lots of things go wrong. You go up the cost curve, down the availability curve, and round the spiral of doom.

Three ways to maintain fleet average age

Fleet management is a capital-intensive business. The reasons for making the investments needed to maintain a balanced, capable and productive fleet are clear. The tough questions are, “How is it done, and how do you attract the necessary capital investment funds?”

Capital is a scarce and expensive resource. Investors of capital are wise and informed. They have options when it comes to investing their funds and succeed by backing winners. Winners develop and use well thought out, simple and convincing plans.

These three tools will help you be a winner in the competition for replacement capital.

1) Buy what you burn, manage stock. This is a simple concept based on the obvious fact that, in order to stay in business, you have to replace the assets you use up in the course of business. If you are a trenching contractor that runs 10 excavators, each of which lasts five years, then you have to replace two excavators per year. If you do not, you are consuming, or “burning,” excavators faster than you are replacing, or “buying,” them.

Comparing the “burn rate” to the “buy rate” for a given class of asset is a powerful, easily understood argument when it comes to showing investors that they need to maintain a given level of investment in order to remain in business for the long haul.

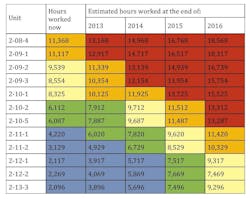

2) Plan ahead. The above chart, the Churn Chart, shows another simple but effective way to illustrate the need for appropriate and ongoing levels of capital investment. The first column shows the 12 units in a particular class or category sorted by their current age in hours worked. The second column shows their current age accentuated by the use of color-coded life zones which show the age of a unit relative to its economic life or sweet spot. Blue is for young machines (0 to 6,000 hours) and green is for machines at or around their sweet spot (assumed to be between 6,000 and 8,000 hours in this case). Yellow, orange and red are for machines that are increasingly older, more expensive, and less capable of achieving production goals (yellow: 8,000 to 10,000; orange: 10,000 to 12,000; red: 12,000 to 14,000). Columns 3 to 6 show the estimated age of individual units at the end of the next four years based on the assumption that the machines will work 1,800 hours per year.

It should not come as a surprise that a machine currently in the green or yellow zone will be in the red or orange zone in a year or two. The chart clearly shows that the age of the group will change from predominantly blue, green and yellow to predominantly yellow, orange and red if nothing is done over the next four years. The chart is a high-impact graphic that enables capital investment to be planned well in advance. There is no doubt that the company in the example will have to invest in seven replacement machines over the next four years if it is to avoid the cost of welding, patching and fixing an over-age fleet.

3) Develop and maintain a watch list. Many organizations develop and use systems that calculate a replacement index for each unit in their fleet and maintain a watch list of machines that are candidates for replacement. The index is calculated using a number of attributes, and systems can be as simple or as complex as you wish in combining various metrics into a single index. Age relative to the sweet spot or economic life is clearly an important metric and often carries a high weighting factor. Reliability, availability and operating cost relative to budget are other frequently used metrics; more sophisticated ranking systems include an assessment of utilization and requirement in the future. Regardless, the system must be well thought out, simple and convincing in order to support a well thought out, simple and convincing capital-replacement plan.

We understand the need for capital investment in our fleet. We know the downsides, struggles and costs associated with deferring capital replacement to levels that make it impossible to maintain the fleet average age we consider appropriate. We need systems and tools to present the facts, develop plans, and succeed in capital budget allocations. The three tools discussed all have their strengths. Develop them and use them to justify and secure required funding.