Equipment fleets represent a large and special kind of capital investment that does not last forever. Machines wear away in the production of work, so there is a constant need for replacement—of both the unit itself and of the capital investment it represents. Maintaining a well-capitalized fleet and generating the funds needed to ensure that it remains reliable and productive is no simple task.

Most equipment managers do not become involved in the details and the complexities of the fleet capitalization process. They know that the CFO’s office charges the equipment account a monthly depreciation charge and work with all concerned to ensure that uptime and fleet utilization are sufficient to recover what they frequently see as an arbitrary and uncontrollable portion of their cost structure. They know that there is a thing called depreciation and that the CFO’s office will charge them for it one way or the other. They also know that a good annual capital expenditure budget is critical for success and work hard to define needs, defend and argue their decisions, and follow through with the approved acquisitions.

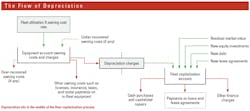

Let’s lift the hood on the depreciation process and go through the accompanying diagram to see how the pieces fit together.

We have long argued for the need to split the equipment account into the owning-cost side of the house and the operating side of the house and then to manage each side with the skill, care, and attention it deserves. This is critically important because operating costs and owning costs are fundamentally different and simply cannot be effectively managed if scrambled together into one cost-recovery rate and one cost-management system.

Our diagram deals with the owning side of the house and on the transactions associated with the owning costs and charges that flow in and out of the equipment account. These are shown in the “bucket” on the upper left. The principal inflow comes from the utilization of the fleet and the owning portion of the rate. The calculation of fleet utilization times owning cost rate can be based on hours worked, months deployed, or any of the many approaches seen in practice. Regardless, there must be a way to charge jobs for the owning costs of the resources they use. The results of this process flow into the owning costs and charges portion of the equipment account where they accumulate and provide the funds flowing out to to meet depreciation charges and other owning costs.

Depreciation charges are levied by the CFO’s office. These are fixed monthly charges that are largely predetermined and calculated according to generally accepted accounting principles. They allow for the fact that the company’s equipment assets are used up in the production of work and that funds must constantly be set aside to write down book values, replace capital assets, and maintain a reliable and productive fleet. If we do not do this, we will be living off our seed corn and will most surely go out of business.

The other owning costs outflow is designed to cover items such as licenses, insurance, and property taxes as well as rental payments on rental units that are managed within the fleet-costing system.

The dotted red and green arrows illustrate that the equipment account is balanced by posting under- or over-recovered equipment costs to the company profit and loss account each year. Over-recovered owning costs are most frequently the result of better-than-expected utilization. Under-recovered owning costs are most frequently the result of less-than-satisfactory fleet utilization.

The gray square in the middle is where we switch from the equipment manager’s world to the CFO’s world. It clearly shows that whereas the equipment manager sees depreciation charges as an outflow, the CFO sees depreciation charges as an inflow. The fleet capitalization account “bucket” on the right is where we assemble the resources needed to maintain our fleet average age and ensure that we have the reliable and productive tools needed to complete work on time and on budget. The inflow from the depreciation charges—which manifest themselves as cash by reducing the book value of equipment assets on the balance sheet—is, in most cases, the main source of required capital. Proceeds from the sale of equipment also generate cash as do new equity investments by shareholders who wish to grow the business and expand operations. New debt in the form of loans secured against the fleet and new lease agreements that give you the right to use the leased assets also provide inflows to the fleet capitalization bucket.

The diagram shows three basic outflows from the fleet capitalization bucket. The first is cash purchases of new or used equipment brought into the fleet as well as funds invested in capitalized repairs. Second are payments made on loan and lease agreements, and the third is any other finance charges. The payments on loans and lease agreements outflow has a dotted line around it to confirm the fact that, as with depreciation charges, these are largely predetermined and fixed when you ink the deal.

Here are the lessons. First, the diagram shows us that maintaining and growing the capital value of your fleet is a high-risk, closely coupled system. At an operating level, risk flows from the fact that the inflow to the equipment account bucket is entirely dependent on utilization. This is frequently a function of hours worked or hours billed to jobs. The principal outflows from this bucket—the depreciation charges—are predetermined and invariably occur on a monthly basis. Field utilization is thus a significant risk. At a financial level, risks come from the fact that the depreciation charges flowing into the fleet capitalization bucket provide only a portion of the funding required for fleet replacement and growth. Accessing the required funds and balancing the risks, costs, and tax implications associated with the cash purchase, finance, and lease decision is a complex, risky, and specialized task. (see “Today’s Rent, Lease, Buy Environment,” December 2017.)

Second, the diagram highlights the fact that depreciation charges and payments on loans and lease agreements are long-term, predetermined commitments. Decisions regarding capital investments take time to work their way through the system and should not be taken on the assumption that the past gives you a blank piece of paper. We will discuss this at length in the next article when we will develop some tools that can be used to make sure that current decisions fit well with the trailing impacts of past decisions.

Last, and very importantly, the diagram shows the difference between the equipment manager’s view of depreciation and the CFO’s view of depreciation. As far as the equipment manager is concerned, it is all about setting an appropriate owning cost rate and driving the utilization needed to meet the monthly depreciation charges levied by the CFO’s. As far as the CFO is concerned, it is a matter of combining the funds flowing from the depreciation charges with other suitable sources of capital in order to fund the capex budget, meet ongoing commitments, and balance cost and risk at a company level. These are two very different responsibilities: Neither is easy and both require skill, care, and attention to detail.

For more asset management, visit ConstructionEquipment.com/Institute.