3 factors that smooth relations between equipment and operations

How do you reconcile actual costs with what is actually charged to the construction project?

Relationships between construction operations and the equipment-management team are often strained. Operations see the equipment they use as a means to an end—as a way to build the job safely, on budget, and on schedule. Equipment managers, on the other hand, see the fleet as a long-term company asset that must be managed with care and diligence throughout its life cycle, regardless of the job or jobs on which individual machines work at any given point in time.

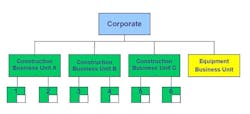

Most construction companies have an organization chart a little like that shown nearby. There are one or more construction business units tasked to build the work and an equipment business unit tasked to centralize equipment expertise and provide the equipment resources needed for success. The jobs, numbered 1 to 6 in the diagram, use the equipment and pay an internal charge to the equipment business unit designed to cover the cost of the equipment resources used on the job. Past articles (See April and July, 2018) describe the complexity of the process, yet internal charges based on internally set internal rates cause internal friction. If I see an internal charge as a cost and you see the same charge as a revenue, then we most likely see the world differently.

Many reasons underlie this difference in opinion, but experience has taught me that three factors cause most of the problems. Get them right, and you are in with a chance; get them wrong, and nothing will work.

Equipment rate and calculation

In the vast majority of cases, the charge paid by the jobs to the equipment business unit is based on an internal hourly, daily, or monthly rate. Operations frequently see this rate as too high due to inefficiencies or bad decision-making in the equipment group. The equipment group sees the rate as a fair and reasonable estimate of the lifecycle owning-and-operating cost of the machine. When the rate is insufficient to cover the actual costs experienced, it blames bad operations, over-application, or various shenanigans such as under-reporting hours worked. There is enough room for everyone to point fingers, and there is enough uncertainty for no one to be right.

The emotion associated with the rate and its importance in the calculation of the internal equipment charge makes it critical that everyone within the organization understands at least three things.

First, decide what is included in the rate and what is seen as a direct-job-equipment cost. Disagreements frequently flow from changes or “special provisions” made for jobs where the material is rocky or abrasive, or where the standard equipment ownership model does not apply. And then, of course, there is the big one: What is and what is not included in the rate for operator abuse, accidental damage, and over-application.

The organization must clearly define what is included in the rate, how it handles unusual jobs, and how it handles back-charges for damage. If not, the arguments will never stop and neither responsibility nor accountability will exist.

Second, define the assumptions behind the rate calculations. Critical assumptions such as ownership period and utilization must be clear and communicated. Decide whether major repairs will be included in the rate or whether they will be capitalized, in which case they end up as an owning cost.

Tabulate the assumptions made in the rate calculation for each class and category of equipment. Know them, understand them, and be in a position to defend them. Know that the accuracy of your calculation depends on the quality of your assumptions.

Third, standardize and communicate the rate calculation. Suspicions abound where the exact methodology is not clear. Simple calculations that show what is included and show what assumptions have been made are best. Complex calculations may be slightly more theoretically correct, but they breed suspicion and undermine confidence.

Have a standard, simple way to calculate, and communicate your rate calculation. It is, after all, nothing more than an estimate based on your ability to predict what is likely to happen in the future.

The minimum-hour rule

No one likes to have machines sitting idle. They are not earning any money, and they are not recovering the fixed costs of having them in the fleet.

Jobs believe they should only pay for the time the machine actually spends working and that idle or standby time should be “free.” Although reasonable, this encourages hording on site and places the risk of under-recovered fixed costs squarely on the equipment group which can do nothing to improve the flow and sequence of work needed to achieve required utilization.

Many companies have a minimum-hour rule where jobs pay for a minimum number of hours per week or month regardless of whether the machine works or not. This addresses the problem of hording and places the risk of fixed-cost recovery on the site where appropriate decisions can be made to either use the machine or return it to the yard.

This rule works to some extent, but it encourages inefficiency. If the job is going to pay for the machine, it may as well use it. The rule also frequently leads to a situation where hours are under-reported in good weeks as a perceived quid pro quo for having to pay for unutilized hours in bad weeks. Many companies use a dual-rate system where sites pay a fixed monthly charge to cover owning costs and an hourly rate times the actual hours worked to cover operating costs.

Make sure that every one understands how a minimum-hour rule works and why the jobs must carry the risk of fleet utilization. Only the site can plan and manage both the work and the resources used to perform the work.

Equipment account gains and losses

In some years, the equipment charges paid by the jobs do not fully cover the actual cost of owning and operating the fleet, and the equipment account runs at a “loss.” In others, job charges will exceed true cost and the equipment account makes a “gain.”

The question is, how do you handle and finally reconcile the differences between job charges and actual costs. It is easy to say that each business unit is responsible for its own budget, and that gains and losses are consolidated at a corporate level. The simplicity does, however, hide at least two problems. First, the equipment charges become a battle ground where business units focus on the games needed to manipulate internal charges rather than the action needed to attack the true causes of equipment costs. Second, construction business unit managers never see or experience the true cost of the equipment used to produce the work they build. The rate becomes synonymous with true equipment cost, and equipment-cost management becomes a process of lowering rates and manipulating reported hours. Theoretically, variances in the equipment-account budget should be allocated back to the sites and business units. This is, in most cases, all but impossible when machines work on short-term jobs and when they move between construction business units.

Re-allocating budget variances to other business units on an arbitrary basis is worse than not doing it at all. Using hard data helps but does not solve the problem. Allocated variances—positive or negative—destroy the commitment and motivation needed to achieve defined business results and negate everything done to measure and manage performance.

The best solution is to know your costs, budget with care, and keep variances to a minimum. Have a well understood plan and policy regarding budget variances. Know that in the end, it is about motivation and management performance. Focus on attacking the true causes of true cost and let the internal charges lie where they fall.

Construction business units and equipment business units are what the text books describe as mutually interdependent. What is good for one is good for the other. Even though they see the world differently, they must not let these differences impact performance. Get the Big Three right and you are in with a chance. Get the Big Three wrong and it will be uphill all the way.