Depreciation is a word with so many meanings that it is all but meaningless. In asset management, depreciation must be defined carefully each time it is used, and there must be a full understanding of exactly how a particular form of depreciation works. We encounter three different types of depreciation: accounting, tax, and market.

Accounting depreciation for assets

Accounting depreciation satisfies two similar but different requirements. First, assets on the company’s balance sheet must be fairly stated. The value of the capitalized equipment assets used by the company goes down with time and usage. There must therefore be a rational and systematic way to reduce, or “write off,” the value of the capitalized assets on the balance sheet so that their “book value” is fairly stated relative to their market value.

For more asset management.

Second, the profit and loss statement must be fairly stated. The cost of capitalized assets must be reasonably spread over the total period for which they are used to produce work. There must therefore be a rational and systematic way to allocate the cost of assets used in a given period to ensure that the profit-and-loss statement (P&L) for the period is fairly stated.

Accounting practice requires that the same “rational and systematic way” be used to satisfy both of the above requirements. Therein lies some of the confusion and tension. If the objective is to ensure that the balance sheet is fairly stated, then the methodology used must try to mimic market values and have relatively high write-off percentages in the early years with lower percentages in the later years. If the objective is to ensure that the P&L is fairly stated from year to year, then the percentages should be the same from year to year on the basis that the productivity of the machine remains essentially the same throughout its useful life.

Individual companies have substantial flexibility in certain accounting decisions, including the following three. The “depreciation period” is the number of years or hours over which the value of the capitalized asset is written off on the balance sheet and/or allocated to the cost of operations. The “remaining value” is the percentage of the capitalized value of the asset that will not be written off during the depreciation period. The “write-off process” is how annual depreciation charges will be calculated for each year or hour of the depreciation period. These three factors combine to define the accounting depreciation policy, which can be different for each class of equipment in the fleet.

The chosen depreciation policy should be easy to administer and should help to ensure that both the balance sheet and the P&L are fairly stated. If it is overly aggressive, annual owning costs will be higher than necessary, leaving the profit in the iron. If it is overly conservative, it will understate annual owning costs and result in rates that are below the true cost.

Tax depreciation for assets

Since depreciation impacts financial results, tax codes include their own clearly defined depreciation policy in order to standardize the depreciation calculation. Tax depreciation is a standardized permitted cost of doing business that recognizes that equipment experiences wear and tear when used to produce completed work. Tax depreciation can be claimed for all assets that are owned by the company, used by the company in the production of income, and have a useful life greater than one year.

The tax depreciation policy spelled out in the tax codes varies with different asset classes and is frequently adjusted by the IRS to incentivize capital investment or further macro-economic policy. Details as to exactly how the IRS calculates the depreciation percentages are beyond the scope of this article.

Market depreciation

Market depreciation is the amount by which the market value of a machine decreases over time and is defined as the difference between the purchase price of the machine and its residual market value when sold. Residual market value is, however, only known when the machine is sold. Therefore, the final cost of the actual depreciation experienced is only known when the machine is sold.

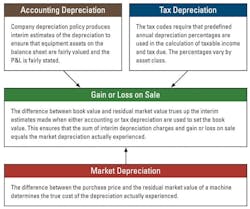

Market depreciation is, in the end, the only number that counts. Accounting and tax depreciation are, in fact, nothing more than interim estimates of what the market depreciation is likely to be. They are used to estimate the value of equipment assets on the balance sheet and calculate income and income after tax during the life of the machine. These estimates must be trued up by calculating a gain or loss on book value once the machine is sold and the final market depreciation can be determined.

The concept of gain or loss on sale is fundamental to the process of demystifying depreciation. It trues up the interim estimates made when company policy or tax codes are used to determine either the accounting or the tax book value of a machine. The process is summarized in the nearby diagram.

Here are five keys to managing owning costs and making better decisions.

Focus on market depreciation. It is the only number that really counts and is invariably affected by many things other than age. The market depreciation likely to be experienced should play a part in the selection decision; should influence the maintenance standards adopted; and must be taken into account in repair, rebuild, or replace decisions.

Accept that annual accounting and tax depreciation charges serve only as interim estimates for market depreciation. Accounting and tax depreciation policies charge a predetermined amount of depreciation to each year of ownership but do not affect the final cost of depreciation.

Maximize the rate of tax depreciation to claim the maximum deductions as soon as possible when calculating taxable income. Tax shields generated by large early deductions will reduce tax liability in the early years of ownership. They may have to be “returned” later, but the company would have had the benefit of the cash flows and the time value of money.

Set accounting depreciation rates to match market depreciation as closely as possible. Reducing accounting book values has the advantage of minimizing the possibility of a loss on book value when selling a machine. Be aware, however, that a low book value may set aspirations too low when selling the machine on the open market and result in a less-than-optimum price. Plus, a gain on sale means that the book depreciation is too high and owning-cost rates are overstated.

Track the relationship between depreciation recovered and depreciation charged for a given machine or group of machines, and then set a depreciation recovery rate that will keep them in balance at a reasonable utilization. Recognize that high levels of depreciation recoveries due to exceptional utilization are not windfall gains: The extra hours are likely to impact market depreciation.

Depreciation is a major part of equipment owning cost. It is also among the most difficult to estimate and manage. The amount is not fixed, and no one sends a monthly invoice. Exact depreciation is only known when the machine is sold. Understanding the key principles, the process, and the language used enables equipment managers to focus on the one thing that determines the ultimate cost of depreciation: the difference between what was paid when purchased and what was received when sold.

About the Author

Mike Vorster

Mike Vorster is the David H. Burrows Professor Emeritus of Construction Engineering at Virginia Tech and is the author of “Construction Equipment Economics,” a handbook on the management of construction equipment fleets. Mike serves as a consultant in the area of fleet management and organizational development, and his column has been recognized for editorial excellence by the American Society of Business Publication Editors.

Read Mike’s asset management articles.