Capital expenditure budgets are at an interesting crossroads. Some companies are expanding operations and want to know how much, where and how to invest in their fleets and position themselves for the future. Others see the glass as half empty and are wondering how to minimize expenditure, maintain capacity, and survive for an upturn they believe is still some distance in the future. Regardless, capital budgeting is far from simple, and the equipment investments you do—or do not—make today will play a major role in defining the future of your company.

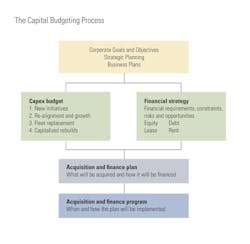

Let’s spend some time understanding some of the challenges and the processes we can use to unscramble the problem and make better decisions. The diagram shows the essential steps.

Capital investments should not be made on a whim. Investment decisions are guided by clear corporate goals and objectives and an effective decision-making process. Competent capital budgeting starts with a clear understanding of the business, where it is going, what opportunities it will pursue, and how it will flourish in the future.

The capital expenditure budget (Capex Budget) must be a well-considered and thought through “wish list” of the capital investments needed to ensure that equipment assets are available and able to support planned operations reliably, efficiently and economically. The budget must be comprehensive, and each item must be justified and prioritized. It is naive to assume that everything will be bought or that everything will be bought for cash. The realities of financial constraints will invariably influence the acquisition and financing plan.

Capex budgets can conveniently be broken down into four sections.

1. Acquisitions and new ventures

The priority given to this section is based on corporate goals and objectives and the availability of strategic business opportunities. Day-to-day needs often conflict with this section, and tempting new opportunities can easily defer required investments in the current fleet. Balance is important, and little is achieved if new acquisitions delay critical fleet replacement needs or make them expensive or risky.

2. Realignment and growth

Equipment assets last a relatively short period, and managers have an ongoing flow of opportunities to review the composition of the fleet and ensure that it is correctly sized to support current business plans and opportunities. The capital budgeting process should be used to conduct this review, and funds for re-alignment and growth should have a high priority. It makes little sense to plan for a new and different future and then not realign your fleet so that it supports the vision.

Decisions regarding which assets to retire and which assets to acquire in the realignment and growth section of the capex budget are based more on estimates of future utilization and needs than on current owning and operating costs. Don’t hold on to units that are no longer needed. If plans show that machines in a certain category will not be utilized, give them a new home; do not keep your money locked up in the bank of under-utilized equipment.

3. Fleet replacement

This section of the capex budget focuses on the expenditure needed to replace units in well-utilized categories that are at or beyond their economic life. Units with low estimated future utilizations would already have been identified in the realignment section of the budget. Decisions here should be based on reliability, availability, operating cost growth, and age relative to estimated economic life.

This is a critical portion of the budget. You are looking at well-utilized categories at the core of your business. It is difficult to imagine long-term success if funding here drops below the value of depreciation recovered from the ownership portion of the rate. If this happens, the company is “living off its seed corn” and the future is bleak.

4. Capitalized rebuilds

This is normally a relatively small portion of the budget that provides for expenditure on capitalized rebuilds and major component replacements that extend unit life and add to the value of the fleet. Properly rebuilding construction equipment is a complex and expensive process that must be undertaken with care. Thought must be given to the performance of the original unit, the integrity of its frame, and to the fact that the rebuild must achieve two things: substantially lower future operating costs and substantially lengthen life.

The realities of financial strategy and the steps needed to maintain desirable balance sheet ratios will invariably require a number of compromises and complex decisions regarding capex priorities and financial realities. What you buy is important; how you finance it is critical. It is, therefore, important to develop a realistic, robust and financially astute acquisition and finance plan. Every form of finance—equity, debt, lease and rent—has its risks and rewards and must be considered. The computations are complex and, regardless of which alternative appears best, the plan will have to consider factors such as:

- The availability of cash and need to maintain working capital and liquidity.

- The debt-equity ratio and the need to reduce long-term financial commitments and maintain defined balance sheet ratios.

- The need to maintain flexibility and minimize the high-risk fixed costs associated with loans and leases.

- The ability to obtain favorable terms and share risks in areas such as residual value by continuing to work with dealers and manufacturers.

- The need to hedge your bets, “try before you buy,” and build equity in your fleet by entering flexible rental-purchase agreements.

The acquisition and finance plan integrates the capex budget with the company’s financial strengths and tax position. It maximizes the availability of funds and reduces risk by assembling an appropriate portfolio of financial resources. The plan requires careful implementation over time. When and how it is to be implemented is detailed in the acquisition and finance program.

The questions, of course, remain: How big should the capex budget be, and how much capex is enough?

Capital investment in a business is entirely dependent on plans and aspirations. If a steady state or organic growth is desired, then the company must “buy what it burns.” It must invest at least enough to maintain fleet average age and realign its fleet to meet changes in the market place. The “buy what you burn” calculation is simple and straight forward. Each year a certain number of machine hours in a given category is “burned up” in the production of completed construction. Each year (or, at least every couple of years), new units must be purchased to replace the machine hours used up. Some companies index their capital expenditure to contract revenue earned in the past year. Others, perhaps more appropriately, index capital expenditure to backlog or new contracts awarded. The company is making capital investments for the future because it is building for the future.

It is not difficult to do the calculations, but it is difficult to develop a comprehensive acquisition and finance plan that supports company aspirations and fits within the reality of financial constraints. You are, indeed, building for the future.