Elon Musk’s Teslas have become mainstream, and consumers will have dozens of electric vehicle choices by the end of this year. Managers of construction equipment fleets already consider electric trucks in their acquisition planning—or at least they should be—and moving electric power choices off the pavement into the dirt is inevitable.

In order to gauge the reality behind the buzz—and to provide a benchmark—Construction Equipment asked equipment managers about electric-powered equipment and trucks. More than 500 responded to an email invitation, and 300 completed the survey. The results reveal an industry unevenly split between those committed to using electric power in their operations, those taking early steps, and those taking a wait-and-see approach.

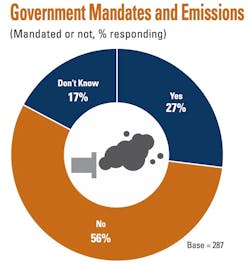

More than half (56 percent) of respondent said that they do not work in areas with mandated emissions limits for construction.

Truck manufacturers, as they did with reductions in diesel emissions, lead the construction equipment manufacturers in putting electric power to work. Manufacturers of aerial lift equipment and compact equipment have fielded some electric-only entries and prototypes, and some heavy machines use hybrid power and electric drivetrains.

Some 85 percent of respondents to the CE survey said that they do not use either electric-only trucks or equipment in their fleets. Four in 10 (41 percent) have no plans to acquire electric-powered construction equipment, and 21 percent did not know whether they would acquire them. Three of 10 (28 percent) said they plan to acquire electric equipment, but not for a year or longer.

“That’s the million-dollar question,” says Bud Fultz, owner and president of Ole South Excavating in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. “We haven’t seen much yet. Technology keeps changing, so if we were to say yes or no, we would say yes, at some point.”

Ole South has a fleet of 39 pieces of equipment and 17 trucks, focused primarily on residential site development. It faces no government or corporate mandates on emissions, and the fleet is stable, Fultz says, with only routine updates and replacements.

Gerald Russell is owner and president of Advantage Grading & Engineering, in Temecula, California, with a fleet of one dump trucks and 10 pieces of heavy equipment. He is not currently considering electric-powered equipment, either.

“The jury’s out on them,” he says. “I’m not the guy going to buy the first thing before somebody else.” Russell has looked at electric vehicles and has rented Caterpillar’s D7E electric drive dozer.

Other fleets are actively pursuing electric power. Clark Construction Group has begun work to lower greenhouse gas emissions among its companies, including Guy F. Atkinson Construction, says Tim Karle, equipment superintendent for Atkinson. Atkinson is a heavy civil contractor with 75 pieces of equipment and 160 vehicles and trucks. Atkinson has some Teslas in the fleet and has placed an order for three Ford 150 Mavericks.

He says Atkinson is working to align with California mandates, including a 2024 stop to the sale of gasoline-powered generators and rules requiring increasing percentages of new-truck sales to be zero-emission. By 2035, 75 percent of Class 4-8 straight trucks sold in California must be zero-emission, according to the state’s Advanced Clean Trucks Regulation (ACT).

Other states—Oregon and Washington on the West Coast and New York, New Jersey, and Massachusetts on the East—have also signed onto the ACT. California is the only state in the union allowed to make air-quality rules that are tougher that federal laws, so what happens there migrates elsewhere. Manufacturers who want to sell equipment and trucks into California will do what they need to do. More states will likely follow.

As far as electric-powered equipment is concerned, Atkinson has not purchased any fully electric equipment because it isn’t yet available, he says.

“We rent our aerial platforms. They have not come out with an electric model yet. When they do, we’ll make the switch.”

Among the limited number of respondents who said that they currently use electric equipment and trucks, 63 percent use in-house charging stations to recharge batteries and 3 percent use public charging stations.

The logistics of charging electric-powered equipment is a major impediment to respondents jumping on the electric train. Lack of a reliable recharging infrastructure was cited by 71 percent of respondents, followed by “inconvenient to charge while on the job site” (66 percent) and “need to recharge during the work day” (57 percent).

EV performance an issue

Mark J. Nahra, P.E., manages the fleet for Woodbury County, Iowa, which is responsible for 1,360 road miles and 300 bridges more than 20 feet long. He has no plans to move into electric-powered equipment because he cannot keep it charged for their applications.

“For us to be operational for an eight-and-a-half-hour day with the geographic area that we have to cover, I haven’t seen electric equipment on the market that would keep us running all day,” Nahra says. “When we’re doing a ditch-cleaning project, for instance, we’ll be out on a road that may be 10, 15 miles away from where our maintenance shed is. That piece of equipment doesn’t come back to the shed every night. It’s one thing to haul diesel fuel out to fuel that excavator and dozer, but we don’t have a place to plug it in.”

Even for electric cars and pickup trucks, Nahra says there is no charging infrastructure to support the distances traveled.

“It would not be practical,” he says. “For my office and inspections staff, we might be able to get by with it. But that vehicle would probably never be able to leave the county. We can drive 100 miles to a project from our office and not leave our county.”

Recharging trucks and equipment that travel long distances requires logistical support, and vertical construction is better suited to an electrified job site than civil or heavy work.

“If you’re building a high-rise structure, it’s a lot easier to have the infrastructure there for electric machines versus a freeway project that spans 13 miles and has multiple work areas,” says Atkinson’s Karle.

Fultz agrees. Construction sites—unlike mines, quarries, or single structures—require on-site power for recharging of equipment.

“Once it’s taken out there, it stays until the job’s done,” Fultz says. “If we’re going to have charging stations to charge this stuff over night, it’s going to have to be field ready. Some of the places we work, we don’t have public power yet because the electric companies run so far behind getting power into places.

“I think...somebody will figure out how this is going to be done. But I think industry-wise, on EV heavy equipment, that’s going to be the holdup.”

Karle also says on-site charging will come.

“I think we’re 10 to 15 years away from an all-electric job site, as battery technology advances and they figure out how to charge the batteries faster.”