No Time for Idling

It’s simple, really. By eliminating engine idle time, equipment-management professionals plug up a big hole that wastes fuel, and simultaneously, they rid the environment of health-damaging pollutants. The rub, however, is to impress on vehicle and equipment operators the importance of turning engines off when work isn’t being done.

During a 2005 meeting of the Great Lakes Regional Pollution Prevention Roundtable in New York, Mike Moltzen, Environmental Protection Agency, Region 2, encouraged fleet professionals to use current technology in addition to operator training to reduce idling time. Moltzen’s recommendations included auxiliary power units, small engines that provide power to the main engine without idling; advanced truck stop electrification for long-haul rigs; and automatic shutdown devices, sometimes called idle limiters. Limiters are timed to turn off the engine, as a rule, after three to five minutes of idle. Moltzen informed managers that federal funds were available to implement such technologies.

Moltzen’s message in 2005: “The Three R’s—retrofit, replace, reduce idling.” Fleet managers have paid attention, including Bill Vanden Brook, CEM, fleet service superintendent for the City of Madison (Wis.).

Vanden Brook installed idle limiters mainly on his on-highway equipment. “That’s where our fuel is primarily consumed,” he says. “Heavy diesel trucks and some of the newer off-highway machines [also] now have idle limiters.”

Vanden Brook says newer computer-controlled engines have a parameter that allows them to be programmed to shut off after a pre-determined amount, such as three minutes or five minutes, of idling.

The shut-down time can vary, says Vanden Brook. “If it’s very cold—like today in Wisconsin, it’s five below zero—you have a different parameter setting. Or you can use ambient air temperature sensors that tie into the idle limiter. As the name implies, the sensors detect the ambient air temperature, and if it is below a certain degree or above a certain degree, shuts down the engine along with the heater or air conditioner. It can also be programmed to continue running, depending on how the idle limiter is set.”

The options are numerous, Vanden Brook says, and they can be as simple or as complex as the circumstances require. Idle limiters are money-savers and cut down on harmful emissions, thus meeting state and EPA standards. But on the down side, they require maintenance that not all fleets can provide.

“Maintenance tends to require more technical knowledge and ability than the old days,” Vanden Brook says, “so technician training plays in pretty heavily.”

Shut down devices can be factory installed when equipment is ordered or retrofitted with a variety of aftermarket products. Vanden Brook plans to follow the retrofit route and use federal funds pay for it.

“We have applied for a $400,000 grant that is available through the EPA,” he says. “This will let us retrofit a fair number of equipment pieces. The grant money not only includes idle limiters, but also other technologies, such as auxiliary power units and dedicated fuel tanks for biodiesel.”

Idle reduction devices will go on 105 units in Vanden Brook’s fleet.

“You could save 105 gallons of fuel a day,” he says. “From an emissions standpoint, you are not generating any pollutants because you aren’t burning that amount of fuel. Also, these are newer technology engines so they burn cleaner than older non-Tier engines. If we can reduce more particulates, we could avoid becoming a nonattainment area [no mandatory vehicle inspections]. We are right on the border.”

If Vanden Brook obtains the federal grant, it will allow him to contract with local equipment dealers to make the change and do the programming instead of relying on his own staff.

Vanden Brook also factored in the return on investment.

“It’s hard to get a true ROI at times because so much depends on the individual operator,” he says. “A very diligent operator who shuts the engine off every time he takes a lunch break doesn’t need an idle limiter.

“But if you have someone who starts the engine at 7:00 in the morning and doesn’t shut it off until he leaves work at 3:00 in the afternoon, then you have an opportunity to save a gallon of fuel a day with an idle limiter. Considering the cost of fuel, it would not take long to get your ROI.”

Idle limiters also eliminate one maintenance service per year for every vehicle, Vanden Brook says, which is about half the cost. He estimates the return could be realized between six months and two years.

Many OEMs have their own idling technology, including Navistar.

“There are some telematic devices that can be installed to remotely monitor a unit,” says Nick Lengacher, Navistar’s product manager, North American Vocational Trucks. “The International system, called AWARE, allows a fleet manager to go into a portal and monitor idle time. It does not give him the ability to remotely shut down the vehicle. There is some liability involved there.”

The International idle limiter system detects when a PTO is activated and the engine is ramped up. “We won’t shut the engine down in a case like that,” Lengacher says.

A fleet manager could also install idle limiters with no problem, Lengacher says. “There is no new hardware to add. Any International dealer with the software tool can install it. Many bigger fleets actually have the software capability to do the installation themselves. Parameters established by the fleet manager are set by laptop.”

Lengacher says fuel savings can be calculated based on a rule of thumb of one gallon of fuel burned per hour of idling.

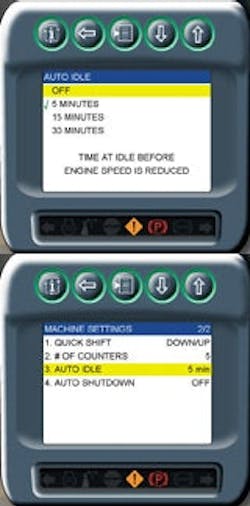

Joe Mastanduno, product marketing manager for engines and drivelines at John Deere Forestry and Construction, says that idle limiters simply have a timer inside that counts time and, at some point based on a pre-set number, kicks in. “With electronically controlled engines, the device monitors what the engine is doing, and takes action.”

Two sets of intervals are generally considered with idle limiters. One is auto idle, when the computer senses the engine has been at idle for a long time and brings the idle down. The second is a timer that takes action only after the auto idle runs a certain amount of time. Auto shut down turns off the machine.

Although it is easier to install idle limiters at the factory, Mastanduno says, a fleet manager can have a third party handle the installation. Since idle limiters are inexpensive ($500 to $1,000) the ROI is quick, especially with escalating fuel prices.

“It depends on how you train the operator,” he says. “In effect, it forces the operator to get out of the cab, not sit there having lunch with the engine idling.”

Among the studies conducted by Deere, Mastanduno says some show that certain types of machines idle 30 percent to 40 percent of the time.

“Loaders, for example, waiting for the next truck to come in, fall into that category,” he says. “You have to look at each machine and calculate how much time the machine is idling. If it falls into that 30-to-40 percent category, you can realize an immediate reduction of 30 to 40 percent in fuel costs.”

Shut downs, however, shouldn’t catch the operator off guard. “You don’t just want to let it happen,” Mastanduno says. “The guy may be into the next operation and you don’t want the machine to just cut out. You have to have data coming back to keep your guy informed.”

Although each OEM has its own idle limiter designed for its specific engine, Mastanduno says, “when a customer buys the engine, he buys the computer along with it. The computer comes with a package and in it is the software for the idle limiter. The auto idle limiter is in that software package.”

Sam Houston, CEM, and division chief fleet manager for the City of Jacksonville (Fla.), says if all vehicles, on- or off-road, are thrown into the mix, they idle, on average, 25 percent of the time. “That’s significant when you consider that an hour of idling is equivalent to 30 minutes of driving,” he says.

Houston says he could save about $150,000 to $200,000 a year if he could get his operators (except fire truck drivers) to cut down on unnecessary idling.

Although he is not yet using idle limiters, Houston has instituted a policy prohibiting engine idling. Backed by Jacksonville’s mayor, he has met with all department heads, asking them to enforce the new policy. He has sent out a flurry of e-mails to all vehicle coordinators. He has made up special cards to post in operator cabs, and nearly every vehicle has a bumper sticker with a phone number for citizens to use in reporting vehicles not following the no-idling policy.

The message is clear, Houston says. “We are policing you. We are watching you. We are going to stop idling.” He’s hopeful his operators and drivers will “do the right thing and I can get the results I want voluntarily.” If not, he’ll start looking at idle limiters.