Have you ever thought about what you are doing when you walk to the rental car aisle at the airport, pick up a car, drive to the gate, check out, and continue on your way? It seems so simple, but a lot has happened. The rental car company has just given you the right to use one of its cars for a stipulated period at an agreed price subject to an agreed set of terms and conditions. You set the stipulated period, and you know the agreed price. As a frequent customer, you did read the terms and conditions many years ago when renting cars was a novel experience. It is simple, but under the hood—if you will excuse the pun—it is a complicated, fairly risky transaction.

Recent changes to regulations relating to leasing equipment have brought the term “right to use” into our day-to-day vocabulary. It is a term that should be used more frequently and in a broader context.

What is 'Right to Use'?

What are you doing when you put a company-owned excavator on a low boy and send it out to a job site? You are, in fact, giving the job the right to use the excavator at a given rate for a stipulated period. As we saw with the rental car, however, every right-to-use agreement is—or must be—subject to certain terms and conditions.

Your job sites are frequent customers. The rate has been agreed and there may have been some discussion regarding the period. I am pretty sure that you do not have two pages of fine print setting out the terms and conditions under which the company gives one of its jobs the right to use one of its excavators. The terms and conditions are, sort of, understood but few, if any, are written down.

Read also: Residual values impact equipment life decisions

Let’s think about a few of these “implicit” terms and conditions. You will put a trained, safe, and qualified operator on it. You will use it for the purpose intended. The operator will do the daily checks, and it will be made available for scheduled maintenance. You will pay for a minimum number of hours a week. Damage other than normal fair wear and tear will be repaired and charged to the job. You will, within reason, adhere to the stipulated period and give a week’s notice of any change. You will pay for sending it back to the yard.

It is assumed that the company’s terms and conditions are well understood. They are, however, seldom explicit and are frequently misinterpreted under the guise of “we have always done it this way.”

What terms define right-to-use agreements?

It is critical to understand that every right-to-use agreement comes with its own set of terms and conditions. These can be implicit—we have always done it this way—or explicit—here is the fine print. The real value of this concept comes from the fact that terms and conditions are often more important than price and can be a significant source of risk.

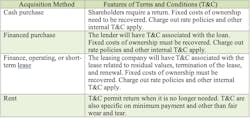

Buying a machine, taking title, and putting it on your balance sheet as an asset does not mean that there are no terms and conditions associated with its use. Your shareholders have used their cash to acquire the rights of ownership, and, like the car rental company, they have some expectations of a return. Yes, it is your asset, and, by and large, you can use it as you wish. But it is also a significant investment that must be put to work and utilized as intended in order to justify the decision and produce the required return. Do your terms and conditions acknowledge the fact that it must achieve minimum levels of utilization to recover the fixed costs of ownership and that it must be operated and maintained with skill, care, and diligence? You are in for the long haul: The optimum hourly rate only occurs if you keep it for the optimum ownership period.

If you are not sure that you want to or can make the cash investment, can you consider financing the purchase? You will have the right to use the machine as before, but rest assured, the lending house will have a lot of fine print regarding duration, monthly payments, early termination, and the like. The amount of cash needed to buy the machine may be reduced, but the terms and conditions imposed by the lending house will significantly increase the risks.

You can also acquire the right to use the machine by entering into some form of financial, operating, or short-term lease. The lease house will have its terms and conditions. They are likely to be complex, especially those regarding residual values and early termination of the lease. You will not hold title to the machine, and you will not be able to claim depreciation allowances in the normal way. The right-to-use agreement will be seen as an asset on your balance sheet, while the contractual commitment you have made to pay the lease will be seen as a liability. Again, the terms and conditions of the lease will create risks. These will have to be balanced against the cost, availability, and flexibility of the lease.

If you are not sure that you are in for the long haul, you could acquire the right to use the machine through a short-term rental agreement. As with the car at the airport, the main attraction is flexibility: You can take it when you need it and drop it off it when you are done. It may cost a bit more, but it sure is convenient. And you do not have to make monthly car payments when business takes you to another city.

Read also: Three steps to a machine replacement decision

Every option—buy, borrow, lease, or rent—comes with its own set of terms and conditions. Every set of terms and conditions comes with its own risks. The skill lies in balancing the risks associated with the various ways in which you can acquire the right to use the machines in your fleet.

An emphasis on “right to use” rather than “own” also introduces some interesting thoughts regarding the way in which you define and calculate owning costs. Long ago, owning costs were defined as “all the costs associated with owning a machine and keeping it in your fleet.” This was expanded to acknowledge that not all machines were “owned,” and the definition became: “all the costs associated with bringing a machine into your fleet and keeping it there.”

This left you with the feeling that you were going to “keep” the machine. This is often not the case. The construction industry is changing faster than ever, and we need to adjust the size and composition of our fleet much more frequently than in the past.

Perhaps we should redefine owning costs as “all the costs associated with acquiring the right to use a machine for as long as you wish.”

Sort of what happens at the rental isle at the airport: You need your own car for day-to-day operations, but you also need the flexibility of a short term rental when the occasion demands.

About the Author

Mike Vorster

Mike Vorster is the David H. Burrows Professor Emeritus of Construction Engineering at Virginia Tech and is the author of “Construction Equipment Economics,” a handbook on the management of construction equipment fleets. Mike serves as a consultant in the area of fleet management and organizational development, and his column has been recognized for editorial excellence by the American Society of Business Publication Editors.

Read Mike’s asset management articles.