Fleet’s Effect on Organizational Profit

Should the shop make money?

It is surprising how often this question is asked and how much emotion is attached to almost any answer. Perhaps another way of looking at it is to ask, “Should the shop lose money?”

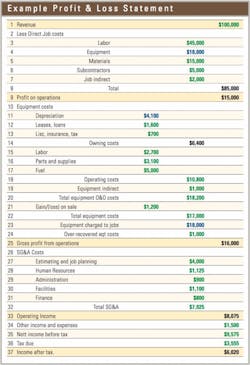

By “shop,” I assume we are talking about the equipment account. By “make money,” I assume we are talking about a process whereby the internal charge-out rates and cost-recovery mechanism are designed to recover more than the estimated true cost of the equipment: The equipment account “makes money” by charging more than it costs to run the fleet. The way the pieces fit together is complicated and best understood by working through the standard construction company profit-and-loss statement shown on the next page. The format used in your company will differ, but the principles and processes will be the same. Let’s divide our review into three parts and take some shortcuts to keep things simple.

Profit on operations

Line 1 is the revenue generated in the period: what your customers paid you for the work you performed. Lines 3 to 7 are the direct job-level costs of performing this work split into labor, equipment, materials, subcontractors, and job indirect as the principal cost types involved in field operations. Notice that the figures for labor, materials, subcontractors, and job indirect are green. This is because these are true costs: The money was spent and paid, it is out the door. Notice that the figure for equipment is blue. This is because the $18,000 is not a true cost; it is an internal charge based on the internal charge-out rates and cost-recovery mechanism used by the company.

Therefore, profit on operations (line 9), or job margin, is the revenue earned minus the direct costs and charges for the resources used to earn this revenue.

Gross profit from operations

This is where it becomes slightly complicated and where we “true up” the $18,000 internal charge made for the equipment used on jobs. Lines 11 to 14 show the owning cost of our fleet. The figures for leases, loans, licenses, insurance and tax ($1,600 and $700) are green because these are true costs. Depreciation is blue because this is again an internal charge that we levy against the equipment account to allow for the fact that assets with a finite life and decreasing value have been used to produce the $100,000 worth of contract revenue. We will true up this blue number when we discuss line 21.

Lines 15 to 18 give our operating costs. No fuss here, these are the true costs experienced as a result of putting the machines to work and earning the contract revenue. Line 19, equipment indirect, is also a true cost. This gives line 20, the total cost of owning and operating our fleet for the period based on the estimated depreciation charge of $4,100.

We do, in the normal course of events, sell used equipment on the open market where we receive its true residual market value. This may be above or below our depreciated book value, and we may experience either a gain or a loss on the sale of our equipment assets. This gain or loss on sale is given in line 21 and serves, to a certain extent, to true up the internal depreciation charges we have levied against our equipment assets in line 11. Line 21 thus serves to adjust the blue value in line 11 and cause our internal depreciation charges to be more market-related. If internal charges are too high, we will recover the unnecessarily high charges through a gain on sale at the end of the life of the machine. If they are too low, the opposite occurs and we have a loss on sale.

Line 22 shows the $17,000 total equipment cost for the period and is obtained by deducting the $1,200 gain on the sale of equipment in line 21 from the $18,200 total owning and operating costs and charges experienced in line 20.

Line 23 is where we take out the blue money we put into the calculation when we charged the jobs $18,000 for equipment in line 4. Line 24 trues up the difference between costs experienced ($17,000) and costs recovered through charges to jobs ($18,000). It shows, in this case, that we have over-recovered equipment costs by $1,000.

Line 25 shows that gross profit from operations is $16,000: the profit on operations of $15,000 plus the over-recovered equipment costs of $1,000. One point of view is that the shop has “made money”; another is that the jobs have been over-charged.

Operating income and income after tax

Lines 26 to 32 show the selling, general and administrative costs (SG&A), or overhead, of $7,925 to give a operating income of $8,075 in line 33. Lines 34 to 36 give the additional amounts subtracted to give us the income after tax of $6,020 in line 37.

Let’s consider now that the equipment costs (the rates used and the internal equipment charge-out process) charged to the jobs was only $8,000 instead of $18,000. Profit on operations would be $10,000 bigger, and we would think things have gone very well because we have made a profit on operations of $25,000 on $100,000 worth of work. We would, however, have under-recovered our equipment costs by $9,000 instead of over-recovering them by $1,000. Gross profit from operations would remain exactly the same, and most of the $25,000 calculated as profit on operations would be a mirage. The tragedy would be if the miscalculated margin and understated equipment cost were to be seen as real and we allowed this to work its way into the benchmarks we use to estimate the cost of future work. We would win a lot of bids, and we would slowly but surely give away the farm.

The opposite is true. If we overstate our equipment costs and bill the jobs heavily, we would reduce profit on operations but over-recover equipment costs. We would not give away the farm by selling the fleet at a loss, but we could easily be less than competitive at the bid table.

Of course, the right thing is to know your costs and to manage your rates and internal equipment charge-out process so that it produces a result as close to breakeven as possible. Be careful and be conservative. There is a lot wrong with the shop losing money, with margins being a mirage and with giving away the farm. There is not a lot wrong with the shop making a little money and with you over-recovering equipment costs. We all like to do our bit to maintain margins and grow the gross profit from operations. Bid markups can be adjusted to allow for any known and predictable margins in the equipment rates, and there is no reason why conservative rates should reduce the ability to compete at the bid table.

Should the shop make money? Yes, a little. It stops our margins from being a mirage, and stops us from giving away the farm. It makes it possible for all of us to contribute to gross profit from operations. We do, after all, all work for the same business.

Learn the fundamentals of fleet management from the collection of Mike Vorster’s video tutorials.