Prevention Is Better than Cure

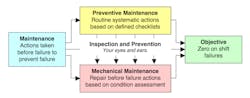

When a machine starts a production shift, it should work without interruption, not break down and not bring everything to a grinding halt. Our goal should be to have zero on-shift failures - it is possible, desirable and it makes good business sense.

Successful equipment managers know that their organization must reduce unscheduled field breakdowns and improve reliability. Maintenance programs must be uncompromisingly thorough, repairs and rebuilds need to be performed to strict quality standards and replacement decisions must be timed to ensure that the fleet is as reliable as possible. Good managers emphasize prevention rather than cure and understand that maintenance actions taken before failure are more cost effective, less disruptive and easier to manage than repair actions taken after the machine has broken down and defined both the time and place for the urgently required repair action.

On the other hand, many believe that replacing components and taking action before failure is a conservative and expensive thing to do. If a component is supposed to run 5,000 hours, why replace it at 4,500 hours; let it run to failure. It may last 6,000 hours; why waste the chance of 1,500 hours more component life?

Repairs are easy. The machine is broken and it needs to be fixed right now. All you can do is spend the required amount as effectively as possible under crisis conditions. It is like opening your parachute after jumping out of the plane –a necessary reaction to a current problem – and you hope for a safe landing.

The worst thing about a repair is the collateral damage caused by the breakdown. A $500 bearing can ruin a $7,000 transmission, $100 hose can cause a $2,000 loss in production. Collateral costs are extremely difficult to measure, they do not appear in cost reports and are often the subject of bitter debate. Regardless, there is no doubt that they exist and that they have a huge impact on both cost and productivity. We simply can not afford equipment failures if we want to hold our heads high as equipment managers and if we want to complete construction on time and on budget.

Maintenance is defined as those actions that are taken before failure in order to prevent failure or extend life. Effective programs comprise two different but equally important components. The first, - preventive maintenance - requires discipline. Routine systematic actions are defined in maintenance check lists, timing is set by the maintenance cycle and work is performed according to a preset schedule. Spending can be seen an investment rather than a cost and without effective preventive maintenance you truly can not expect to succeed. The second component – mechanical maintenance –requires courage. Repair before failure actions are performed to replace components before they fail based on reliable information, condition assessment and a belief that prevention is better than disruption and the collateral costs associated with an on shift failure.

It is possible to run a fleet based on a good preventive maintenance program and then letting a component run to failure before taking any additional action. Managers who do this neglect the collateral cost of lost production, disrupted operations, increased repair costs and crisis management. In exchange, decisions are simple – the machine must be repaired and the money must be spent. The only decisions that need to be made are how to schedule the inevitable overtime, reduce the inevitable cost and whether or not to use the downtime as an opportunity to replace any additional components that appear to be “tired”.

The need to manage equipment costs without sacrificing reliability forces equipment managers to implement a mechanical maintenance program that focuses on repair before failure and bridges the gap between preventive maintenance and repair. This is more easily said than done. It requires courage and a firm commitment to excellence in the management of the fleet. Let's see how it works;

What must be done is determined by a knowledge of component lives, machine history and the current condition of the machine. There has not been a breakdown to define exactly what needs to be done.

When it must be done is your call. It can be done now or a little later depending on your assessment of the risk between the cost of taking action too early in the life of a component and the collateral cost of a failure in the field. Again, a failure has not occurred to force the decision.

How much should be spent is dependant on your decision on the components to be replaced and the work to be done. Doing it this month would be good but how about doing it next quarter when the budget situation should look a little better?

Our ability to implement an effective mechanical maintenance program therefore depends on our ability to predict failure and base decisions on good information rather than conservative guesses. This means we must use the very best tools and techniques available for inspection and condition assessment. The technicians performing preventive maintenance are the manager’s eyes and ears. They visit the machines regularly and must have the time, training and tools needed to inspect and report not just check, change, adjust and lubricate. They must provide information and we must use it to thread the needle between conservative decisions that increase component costs and risky decisions that increase the chances of on shift failure and collateral costs.

Critically important issues

First. We can and should set zero on shift failures as an overall goal for the maintenance and management of our fleet. It is a simple metric, straightforward and achievable. Skeptics should look to what has been achieved in construction safety in the years since we started to believe that accidents were not inevitable.

Second. We need a routine systematic preventive maintenance program based on checklists and schedules to perform routine actions, solve small problems before they escalate into failures and collect the condition assessment data needed to run a cost effective mechanical maintenance program. Preventive maintenance is not a science, it is a discipline. Without it you simply can not expect to succeed.

Third. We need the courage, conviction and confidence to implement a repair before failure mechanical maintenance program that bridges the gap between preventive maintenance and repair. This will require an increase in the amount of effort placed on inspection, oil sampling and other diagnostic techniques that detect impending failure in expensive components and remove the nagging doubts about whether or not the transmission could run an extra 1,000 hours before failure.