Reducing the Impact of Impact Costs

We all know that breakdowns cost a lot more than the parts and labor needed to fix the machine and return it to work. We know that there are consequential costs—or, as we will call them in this article, impact costs—associated with breakdowns and that these often dominate thinking when it comes to the maintain/repair/rebuild/replace decision. The big question is: How do we quantify, or even attempt to quantify, the impact costs associated with lack of availability and downtime?

I have been in this business for a long time and have struggled with the question for more years than I care to count. As with most interesting and complex questions, there are no right answers, only intelligent decisions based on a good understanding of the underlying principles. Let’s use an example to help us unravel the problem. It focuses on the operational level and neglects impacts on the project as a whole. But don’t worry about the details; focus on the principles.

Suppose we have an excavator loading four trucks hauling material to a spoil area where a dozer is working to keep things in order. It is a typical job site with a competent and capable superintendent planning and looking after several similar operations. Suppose now that our excavator breaks down. The trucks return to the load area, and the dozer operator stops work wondering when the next load will arrive. Everything comes to a halt.

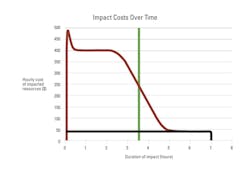

The red line on the impact cost diagram above shows what happens by plotting the hourly cost of impacted resources on the vertical axis and the duration of the impact on the horizontal axis. Impact costs spike to an all-time high immediately after the impact as machines keep running and people wonder what to do. Folks soon realize that this is going to take a while to fix and switch off their engines. The hourly cost of the impacted resources comes down a little. The excavator operator calls the superintendent and the mechanic. Everybody starts working to mitigate the problem.

The site is large and dynamic. The superintendent is capable and flexible. He starts implementing his contingency plans after a relatively short two hours. One truck is sent to the shop for an overdue PM service, one is sent to the loader crew that is a little under-trucked, and the last two are sent to fetch stone for the pipe crew. The hourly cost of the impacted resources comes down as shown by the red line. The contingency plans are not as efficient as the original plans, however, and impacts due to the breakdown of the excavator linger for most of the rest of the shift (five hours). Once the re-planning and reassignment of resources is complete, the hourly cost of the impacted resources drops down to the black line, the hourly owning cost of the excavator itself ($40). This continues until the machine is repaired (7 hours) when they finally go to zero as wheels start rolling again.

Let’s look at four important lessons:

1) We experienced a failure, and there were impact costs. The sum involved is given by the area under the red line.

2) The hourly cost of impacted resources, represented by the height of the red line, is critical. There was the excavator itself, four trucks and a dozer. Impact costs for the excavator would not have been as high if it was working on its own excavating a trench. They would have been a lot higher if it was loading more trucks or if the trucks were involved in a fill operation with a full compaction spread.

3) Flexibility and reaction time, represented by the green line that measures the speed at which we could lower the red line, are equally critical. The availability of contingency plans and the speed with which resources can be reassigned are important. The red line would have run horizontal for the full 7 hours if we were not able to re-plan operations or if the machine involved was the one and only dozer on site capable of push loading our scraper spread.

4) Regardless of how big or how small the associated crew costs are and regardless of how short or how long the site reaction time is, we experienced impact costs because, and only because, we had an unplanned on-shift failure. The vast majority of our impact costs occurred within a short time of the impact itself and were independent of the duration of the impact. We may not know the shape of the red line, but we do know that it shoots up immediately as the machine breaks down, stays like that for a while, and then comes down.

Here are the principles and what we can do to minimize impact costs.

First: Look closely at the cost of the impacted resources and see what you can do to reduce the coupling or interconnectedness between resources. This is not easy as we like to use crews that are as small and efficient as possible. Machines that are “tightly coupled” to the productivity of the crew (an excavator that loads the trucks, a pusher that loads the scrapers, or a transfer buggy that controls the paving spread) must be as reliable as possible. Machines that are not tightly coupled to the production of the crew (trucks in a spread or a dozer stockpiling material) are not as important. Look into the coupling between resources, understand the hourly cost of impacted resources, and manage critical resources with the care and attention they deserve. Do what you can to move the red line down.

Second: Look closely at site reaction time. Build flexibility into the planning process and make sure that contingency plans are available. Consider communication on the site, taking into account how big or remote the site is, in order to be able to re-plan or reassign impacted resources. If you cannot do much because there is nowhere else to send the trucks when the loader goes down or because there is nothing that can be done when the paver goes down, then it is about the speed and responsiveness of your repair crews and dealer support. Do what you can to move the green line to the left.

Third, and most importantly: Impact costs, at a crew or project level, arise because you have experienced an impact. The cost of each impact is important but difficult to measure. The number of impacts you experience determines the total cost and is easy to measure and manage. It sounds silly to say it but if you want to manage impact costs, you must manage impacts. Reliability holds the key. If you want to measure and manage impact costs, start by measuring and managing reliability. Drive for zero on-shift failures. Do your oil analysis, do your preventive maintenance, train your operators, and operate your equipment within its limits. You know the list.

It is extremely difficult to measure impact costs with any sort of confidence. Machines work in all sorts of configurations, and the hourly cost of impacted resources varies from day to day. Site reaction time and flexibility also vary and are difficult to define. But we do know that the total impact cost we experience depends on the number of impacts that we experience. These are easy to measure and manage.

Manage and eliminate impact costs by managing and eliminating the unplanned on-shift failures that are the root cause.