Bottom line—no matter what large CTLs do, this skid steer size class isn’t disappearing, or even contracting, anytime soon.

“The market for 2,200-pound-plus rated operating capacity skid steers is on an upward trend,” according to Kelly Moore, Manitou Group (Gehl/Mustang) product and training specialist. “In particular, loaders in the 2,201- to 2,700-pound category were the largest class of skid steer loaders sold last year, making up around 44 percent of the market.”

Moore says the demand is driven by customers’ desire for added horsepower, increased lifting capabilities, higher lifting heights, and more hydraulic capabilities for attachments. Almost on cue, Moore’s company recently released the latest beefed-up versions of what it touts as the largest skid steers available in the industry, the V420 (Gehl) and 4200V (Mustang), with 4,200-pound ROCs.

“From a John Deere perspective, sales for 2,200-pound-plus ROC skid steers are up roughly 12 percent,” says Gregg Zupancic, Deere’s product marketing manager for skid steers and compact track loaders. “We’re seeing a growing trend of customers purchasing larger machines driven by the versatility of these models. Customers who originally purchased smaller skid steers are moving up into higher-performance models, as they see the ROI a larger machine can provide.”

“If you dissect the population,” says Jorge De Hoyos, senior product manager, skid steers and compact track loaders, for Kubota, “you find that the biggest climber has been those with capacities of 2,700 to 3,150 pounds, which has nearly doubled in size, up to almost 12 percent of the skid steer market.

“There is a fine line between ROC and engine horsepower that brands use to divide their offerings,” De Hoyos says. “Historically, the larger ROC value, the higher the horsepower, but given today’s stringent emission requirements, we find a large population of skid steers with 74-horsepower engines, which puts them right under the threshold of needing to install an aftertreatment that includes SCR and DEF.”

De Hoyos says that by staying under the 74-horsepower threshold, additional cost can be avoided. “Therefore brands are pushing the 74-horsepower engines’ threshold to higher ROCs,” he says. “This helps explain the migration to higher ROC in the 2,700- to 3,150-pound segment, and some manufacturers have even pushed the 74-horsepower engine models to the 3,150-pound-plus ROC segment. Avoiding SCR and DEF can help create a more attractive price to the customer.”

Regardless of pricing concerns, the migration to compact track loaders continues to take a bite out of skid steer sales. Lars Arnold, global product manager, skid steer loaders, for Volvo Construction Equipment, puts the movement in perspective.

“In 2012, the market was approximately 60 percent skid steer and 40 percent CTL. By 2017, that had switched to 40 percent skid steer and 60 percent CTL. I would attribute this largely to more CTL size classes being introduced over the last five years,” Arnold says.

Manufacturers had mixed responses when CE asked if the popularity of large CTLs has affected their large skid steer offerings.

“[Large CTL popularity] has definitely affected the number of models we offer,” says Hugo Chang, product manager for LiuGong. “Rental houses that we talk to have expressed serious interest in our 385B, which has an ROC of 2,300 pounds, and in a model a bit smaller that we plan to introduce to the U.S. market later this year, but we have seen no real interest in anything larger than 2,300 pounds.”

De Hoyos says there is “no doubt” his company has to consider the popularity increase of heavy-lift CTLs going forward. “[These CTLs] are often tagged with the higher horsepower engine. For example, Kubota’s 3,200-pound ROC SVL95-2s, equipped with a 96-horsepower engine which is packaged with an SCR and DEF emission aftertreatment, has been well received, exceeding our expectations. Currently, Kubota does not have a wheel model with this engine package or ROC. Should we ever decide to release a model with increased lift capacity, we have to carefully consider how we power that model,” De Hoyos says.

“Larger CTLs really have not affected demand for our larger skid steer loaders to this time,” Manitou’s Moore says. “Granted, the highest end of CTL units garner more business because of their sheer size, lift capacity, and power from tractive effort. Longer term, if the CTL market continues to trend upward, this could have more bearing on larger-end loaders and their designs.”

Arnold points to specs as a defining point between the two machines, as well.

“It’s true that a CTL’s ROC is 35 percent of tipping load compared with a similar skid steer being rated at 50 percent of tipping load, and that gives the CTL better stability,” Arnold says. “But there will always be a market for skid steer loaders, and they’ll continue to be the top choice in certain applications and price points.”

Manufacturers urge managers in the market for large skid steers to take a critical look at machine size.

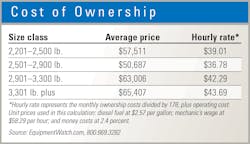

“Often, the larger the skid steer the higher the engine horsepower,” says Jeff Brown, compact construction product specialist for Caterpillar. “Above 74 horsepower requires DEF and will also drink more fuel. So the key is to see if you can do the majority of your jobs without jumping to a high-horsepower unit, which will save in operating costs.”

Buck Storlie, ASV’s testing and reliability leader, also focuses on size. “One of the first considerations when looking at purchasing a large skid steer is whether the size is appropriate for the type of job sites you typically operate on. If you work in tight spaces, such as urban areas, make sure the machine you choose won’t be a constant headache to manuever. Also note the larger the skid steer, the larger the truck and trailer required to haul,” Storlie says.

Managers should also think about attachment capabilities.

“Plans to run high-flow attachments should be considered at the time of purchase, as you typically can’t add high-flow options once you own the machine,” Deere’s Zupancic says. “Customers should purchase the model that has the minimum gallons-per-minute flow that matches their desired attachments.”

LiuGong’s Chang agrees. “Mismatching the attachment to the machine’s capability, particularly the machine’s hydraulic capability, results in disappointment on the part of the user,” he says. “Make sure the hydraulic flow can do the desired job.”

Manufacturers have advice on power, as well, and a few of the common mistakes they see in the field.

“On skid steers, we see people maxing out the capacity,” says Wacker Neuson’s product manager for loaders, Brent Coffey. “Everyone wants the maximum capacity for the least amount of cost. As a result, we see a lot of smaller machines with oversized buckets and attachments. It may work fine when new, but that machine will age much faster and see failures much sooner.” Coffey says.

“Unless exterior noise levels or fuel conservation is paramount, skid steers should be operated at full engine rpm,” De Hoyos says. “This is recommended for hydrostatic machine efficiency, and is especially true when the model is equipped with a DPF. By running the machines at high rpm, the DPF will auto-regenerate, increasing the filter lifespan and reducing the potential of filter clogging that can require removal and cleaning.”

Finally, pay attention to how tires are treated and selected.

“Counter-rotations, or sharp changes in direction, cause premature wear, especially when driving over highly abrasive material, such as shale, granite, or demolished construction materials,” Storlie says. “And, encourage operators to use three-point turns to avoid cuts in the tires often caused by counter-rotations. Users should also avoid spinning the tires, especially on abrasive surfaces. Like counter-rotations, spinning can cut the rubber and cause unnecessary wear.

“Also consider what tire is best for each application,” Storlie says. “For example, a smooth, solid tire is most effective for regular operation on hard surfaces such as concrete, while traditional pneumatic, treaded tires are best for maneuvering over more rugged terrain such as rock and dirt.”

Coffey sums it up best when it comes to operation, and keeping costs down. “A general rule of thumb is ‘Drive it like you were paying for it.’”