It used to annoy me when people referred to the equipment division as “the shop.” That does not bother me now because equipment management is a serious business. It has a huge impact on the company as a whole, providing the tools needed to produce work on time and on budget. Without an effective equipment operation you are not going to get it right.

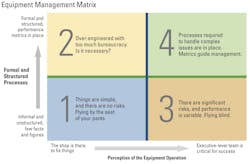

Which perception matches your equipment operation? Is it a shop with mechanics who rush to repair broken equipment and respond to crisis after crisis? Or is it an executive-level team that manages substantial assets critical to the success of the business?

These two perceptions form the horizontal scale in the accompanying matrix diagram. Your organization should lie somewhere in between. The important thing is that equipment management is much more than fixing things. It touches almost every aspect of the business, from operator training and routine maintenance to financial policy and budgeting of capital expenditures.

The vertical scale of the matrix illustrates how formal and structured business and business-management processes are. At one end of the scale, you can have business practices that are informal and unstructured with few facts and figures. Intuition and experience rule the day, and we trust that everyone knows what they are doing. We get things right because we know what is right and just do it. We live in a paradise largely free of paper.

At the other end of the spectrum, we have formal and structured processes. Required data is collected in a routine and structured way, and we have the metrics needed to measure performance. We know where we have been and where we are going. We live in an analytic paradise.

Your business will lie somewhere on this spectrum. There will be some formal processes—people will need to be paid and invoices will need to be processed—but it is unlikely that you will have every fact and every figure you will ever need.

Let’s look at how these two scales interact.

Cell 1. The shop is not perceived to be particularly important: It is there to fix things, and few formal structured processes are in place. This is fine if indeed things are simple and straightforward and if there are no significant risks involved. You are flying by the seat of your pants, so you will have to land your biplane and hide from bad weather when needed. It is not a bad place to be and many small businesses do well in this space.

Cell 2. The shop is not perceived to be particularly important, but there are appropriate formal and structured processes in place. This does not happen often, but when it does it may feel like we are overburdening a simple world with too much bureaucracy. You will have the instruments you need to navigate and will certainly outperform the pilot who flies by the seat of his pants. But you may wonder about the necessity and complexity of it all.

Cell 3 is where you do not want to be. You are running a complex organization critical to the success of your business and much is expected of you. You face significant risks, but you do not have the systems in place to give you the information you need. You are flying blind. Some journeys may finish well and some may finish badly. You are flying a complex airplane without the instruments you need to handle bad weather and things will go wrong.

Cell 4 is where you want to be. The processes required to handle the complex issues of equipment management responsibilities are in place; your team has the stature, training, and talent needed to do its job; and the metrics required to improve performance, reduce risk, and lower variability are in place. You can navigate around storms, and most journeys will be successful.

Three lessons

1) You may be in cell 3 when you think you are in cell 1. You are probably further along the horizontal axis than you think. Equipment management is not a narrow function confined to “running the shop.” It touches almost every aspect of the business.

Good maintenance improves reliability; reliability drives productivity. A good knowledge of equipment costs helps equipment decisions, but more importantly, builds competitiveness and confidence at the bid table. You have to have the processes in place and the information needed to support the full spectrum of equipment-management responsibilities defined in your company. If you are not in cell 1, you must move to cell 4.

2) You may be in cell 3 when you think you are in cell 4. How good is the data you collect, how competent are the analytics you perform, and how good is the information you use to take action? Do you have the instruments, can you use them, and how good are you at navigating in bad weather? Stick and rudder skills are essential, but they are not sufficient when it comes to equipment management in a complex, uncertain, and high-risk world.

3) Move from from cell 1 to cell 4 without going through cell 3. Companies grow, times change, and equipment management becomes more complex. The perception may be that little has changed on the shop floor. We can debate that, but we cannot debate the fact that changes in equipment-management responsibilities have turned the biplane we used to fly by the seat of our pants into a high-powered jet that goes close to Mach 1. We need the procedures, skills, aptitudes, and resources required to succeed in a changed world.

Cell 1 is becoming smaller and smaller. If your company falls to the right of the vertical blue line, it must be above the horizontal green line, firmly

in cell 4.

Construction firms understand the matrix when it comes to project management. We have formal, structured project-management procedures in place, and we devote substantial resources to planning, scheduling, job costing, and performance improvement. We know that we must run construction jobs in cell 4 in order to improve performance, reduce risk, and lower variability.

Why then is “the shop” so often run closer to cell 1 with fewer resources devoted to planning, scheduling, cost control, and performance improvement? Why is a commodity such as fuel managed with less care than the concrete placed in curbs and gutters?

Consider “the shop” as a project. It should rank in size and importance within the organization and have the resources, processes, and information required to ensure success.

For more asset management, visit The Construction Equipment Executive Institute.