Equipment manufacturers often cite differences in design philosophy to claim distinction (and usually superiority) for their products in the marketplace. In the early days of the articulated wheel loader, for instance, manufacturers debated whether placing the operator on the front frame or the rear frame was most advantageous, and both sides of the debate advanced cogent arguments for their design.

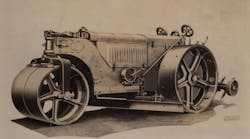

Early in the last century, manufacturers of pull-graders were debating the best design for the machine’s wheels.

In 1885, J.D. Adams, a road inspector, was of the opinion that the pull-grader’s rigid wheels tended to push the machine away from the load on the blade, making the grader inefficient and difficult to control. His solution, when he subsequently developed a pull-grader of his own manufacture, was to design the wheels to lean. Leaning wheels, combined with an angled blade, said Adams, increased the grader’s ability to excavate and move material in a specific direction by forcing the machine’s weight onto the blade, rather than the wheels, thus holding the blade against the load.

Not everyone agreed, however, that the new leaning-wheel design had merit. C.D. Edwards Manufacturing, in a circa-1924 catalog, claimed product distinction and design superiority by emphasizing that “Edwards graders are built with rigid wheels.” Edwards claimed that leaning wheels were needed only to correct for an imbalanced design, and that the “perfect balance” of the company’s machines held them against the load. Edwards went so far as to say that the perfectly balanced, straight-wheel grader was “the greatest development and stride forward over the adjustable wheel.”

Time was the judge of the two designs, and the leaning-wheel concept eventually transformed the grader from a road maintainer into an earthmoving machine. Adams became a traveling salesman for his graders, which were first built for local governmental agencies by a manufacturer he hired. By 1897, Adams had his own factory.

The Historical Construction Equipment Association (HCEA) is a 501(c )3 non-profit organization dedicated to preserving the history of the construction, dredging and surface mining equipment industries. With over 4,000 members in twenty-five countries, our activities include operation of National Construction Equipment Museum and archives in Bowling Green, Ohio; publication of a quarterly magazine, Equipment Echoes, from which this text is adapted, and hosting an annual working exhibition of restored construction equipment. Our 2015 show is Labor Day weekend at Janesville, Wisconsin. Individual memberships are $35.00 within the USA and Canada, and $45.00 US elsewhere. We seek to develop relationships in the equipment manufacturing industry, and we offer a college scholarship for engineering students. Information is available at www.hcea.net, or by calling 419-352-5616 or e-mailing [email protected].