Mention the federal bridge formula law and big, strong truckers cringe. The B Formula, as it's also known, was devised more than 50 years ago to limit gross weight not just by axle, but by numbers of axles (the more the better) and the distances between them (the longer the better).

Maybe you live in such a state and already run seven-axle "Super 18" super dump trucks like the one you see here, and know that they can be a handful to buy and drive. Maybe you're in an eastern state where short, squat trucks are still legal. If legislators ever adopt the bridge formula, this truck is what you'd have to convert to.

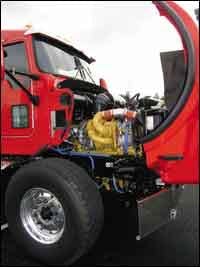

This Kenworth T800 heavy truck would work in most bridge-formula states but was built for Arizona, which has enforced the B Formula for many years, said KW's vocational marketing manager, Stephan Olsen. He had prepared it for my drive on a cloudy, breezy day out of Kirkland, Wash., near Seattle, by getting it shined up and taking it to a nursery for a partial load of topsoil. This made the drive more realistic.

Olsen explained that this super dump truck's main axles are from Spicer: a 20,000-pound-capacity steer axle and a 46,000-pound tandem. Those are physically strong enough to carry the entire load, at least at low speeds off road. On public pavement, there are the lift axles—three 8,000-pound-capacity Watson & Chalin pushers and a 13,000-pound Strong Arm "stinger" (so called because it resembles a scorpion's pain-inducing appendage).

A stinger adds one axle to Formula B calculations and stretches the truck's legal "bridge"—the distance between the first and last axle—by about 15 feet. This gains 9,000 pounds gross, compared to what's allowed for essentially the same truck without the stinger, like they run in Ohio.

In Washington state (as well as in several adjoining states), a long, nine-axle truck-and-trailer may gross up to 105,500 pounds. That makes a Super 18 comparatively unproductive and therefore almost non-existent, so it got some looks as we motored down the road.

Driving the Kenworth Super 18 Dump Truck

That began after Olsen and I hopped in, and I cranked over the Cat C13, lowered the lift axles, released the brakes, put 'er in gear and moved out. As with most Kenworth trucks, I could float-shift the transmission without the clutch right off the bat. But on any unfamiliar truck, it's better to double-clutch to avoid damaging anything, and that's what I usually did.

First gear was enough to get started on any level pavement, though I used Low on any upgrade and 2nd or higher on a downhill. I never needed any of the low-low-range ratios in the Fuller 8LL transmission, and 8th gear allowed leisurely cruising on highways. From the shotgun seat, Olsen directed me onto the I-405 freeway, then out on state highways that included some serious upgrades and ran through a couple of small towns.

Cat's 430-hp ACERT C13 has plenty of power and torque to make most climbs with little downshifting. This engine pulls strongly as it lugs down to its torque peak of 1,200 rpm, where it makes 1,650 lbs.-ft. The boost gauge showed a maximum of about 42 psi from the two turbochargers during one stiff climb where I had to downshift twice.

There was no whistle from the turbos, and none from the air intake. This proved that the strong whistling I heard in a C13-powered Peterbilt 357 a few months before came from the truck's air intake and not from the turbos.

During the drive, I backed up several times and made one laborious U-turn, so I can describe how this beast maneuvers. Driving any straight truck is easy, but it's sometimes ponderous with a Super dump truck. Even with a setback front axle it has a wide turning circle, which makes it a bit clumsy to corner; you've got to remember to spin the steering wheel fast as you begin a turn or you'll go into it wider than you want.

When preparing to back up, you have to raise the stinger axle before reversing, then drop it down as you resume forward travel, unless of course you're going to dump the load. The pusher axles steer themselves while moving forward, but not in reverse. The suspensions depressurize automatically when the transmission is shifted into reverse, so tires don't drag and scuff.

The Strong Arm could probably be wired to automatically raise, too, but this truck wasn't set up that way. When the stinger comes down and takes on its load, you can feel the rear of the chassis rise a little and watch it in the mirror, too.

Most drivers raise all the lift axles as they move onto a jobsite, which requires flipping one toggle switch for each axle. On this truck, all switches are conveniently on the dash so your eyes don't stray far from the road. You definitely want to put down your coffee cup before flipping switches, downshifting and spinning the wheel for a hard turn.

The stinger's toggle has to be pulled before flipping; this discourages you from raising or lowering it unintentionally. Raising it could get you an overweight ticket, but lowering the stinger when the body's empty can jack the drive axles off the pavement and send the truck into "skating" mode as the stinger's wheels caster any way they want to. Wouldn't that be a thrill?

The stinger on this truck runs off a PTO-driven hydraulic pump, and this has to be engaged at times to bring the system up to operating pressure. With the arm down, a gauge showed about 1,800 psi; this dissipates after one or two operations of the arm, and a glowing yellow light warns of low pressure. You then switch on the PTO to run the pump and restore pressure. If you don't, the arm doesn't push its wheels against the pavement and they don't take up their assigned load.

This truck has no in-cab valves to adjust pressure on the axles because state regulations prohibit it. A driver can only raise or lower the axles while underway. Pressure on each axle is preset to take on its prescribed load. On a fully loaded Super 18, it's 5,000 pounds for each pusher and 13,000 on the stinger, plus 20,000 on the steer axle and 32,000 on the tandem drivers.

On this trip, we had only about 15 tons of dirt in the body and weighed about 70,000 pounds gross, so the three pushers alone would've been enough to stay legal. But I kept the stinger down to get the full experience.

If you want to roll over a truck, a freeway cloverleaf is a good place to do it, so I went into such turns at a fuddy-duddy pace, even while remarking during one turn that the pusher axles on this truck probably made it rather stable. Right, Olsen answered, and the W&C suspensions on those pushers are especially good at keeping the truck on an even keel.

Still, the cab's high position on the chassis seemed to accentuate any lateral forces, so I took it easy anyway. Through all maneuvers and over all pavement, the truck rode rather smoothly, even for Olsen who sat on a non-suspended seat.

We also observed that the T8's cab was especially roomy because it has the Extended Day Cab option. This adds a 6-inch extension for the rear wall and the roof is taller by 5 inches. This lets big guys push the seat back for an extra 2 inches of belly room, and recline the seat up to 21 degrees for even more stretch-out space. Kenworth says the extended cab is catching on with a number of customers who want to keep their drivers happy. The longer cab also offers extra storage space behind the seats for tools, lunch, or whatever else a driver might want to carry.

This cab also had the optional corner windows. These add some rear-quarter visibility to a tractor but on a dump truck are blocked by the exhaust stacks and the box. The view to the front was good over the sloped nose, and the Day Light windows with their cut-down sills provided decent visibility to the sides.

The big mirrors have multi-adjustable glass, which should stay fairly clean because of the fixtures' aero-designed housings. Throw in KW's typically legible and readable instruments and well-placed switches and controls in a handsome wood-grain dash, paint the exterior an eye-biting "viper red," bolt on lots of bright-metal trim, and you have a package that pleases most truckers.

One over-the-road driver at a truck stop called it "gorgeous." You may agree, whether or not you like a "super" complement of axles.