Before the advent of slipform paving, concrete paving required the placement of temporary forms to shape the slab. These forms had to be placed accurately, not only to maintain the correct slab width and depth, but also because equipment traveled on them. The dry-batch paver that mixed and placed the concrete could work between or outside the forms, but the machines that spread and finished it rode on the forms like a train on a track.

The forms were placed in a shallow trench on each side of the roadbed and pinned into place. When the concrete was ready, the pins would be pulled and the forms removed. Cutting the trench was, at first, manual labor that could easily disturb the grade stakes and line that controlled grade, and disturbance of the line shut down work while it was reset.

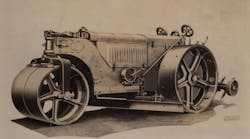

All of this was eliminated by the invention of the formgrader. Details varied between the few manufacturers that produced them, but essentially a formgrader was a tractor equipped with a cutting wheel and an auger. The cutting wheel removed the material from the trench. The operator controlled the depth by raising or lowering the cutter based on a pointer’s position relative to a line strung between grade stakes. The stakes and line had to be set up to 15 inches from the edge of the slab to be poured, but the formgrader moved slowly enough that the stakes were undisturbed.

The cutting wheel was at the tip of a shaft, and much of the rest consisted of the auger. Mounted diagonally under the tractor’s frame with the cutter leading on the left side, the auger forced the spoil across the machine’s direction of travel and windrowed it for spreading or pickup.

Cleveland (Ohio) Formgrader was the more successful of the two manufacturers and built formgraders into the early 1960s when slipform was taking over in earnest. Ted Carr & Co. of Chicago is the only other known manufacturer, building them in the late 1920s and/or 1930s.

The National Construction Equipment Museum in Bowling Green, Ohio, has one of each. Its Carr finegrader rides on steel wheels, with the left rear wheel cleated for traction. Its cutter could dig up to 12 inches deep and wide, and work at 400 to 700 feet per hour. Two crowd speeds, two cutter speeds, and interchangeable cutter blades let it handle anything up to macadam. The Cleveland has tires in front, a crawler at left rear for traction, and a steel wheel at right rear. On both, the right rear wheel is on an extended axle to clear the windrow, and the drive wheel or crawler traveled in the trench to compact it.

The Historical Construction Equipment Association (HCEA) is a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving the history of the construction, dredging, and surface mining equipment industries. With more than 3,800 members in 25 countries, HCEA activities include publication of a quarterly educational magazine, Equipment Echoes, from which this article is adapted; operation of National Construction Equipment Museum and archives in Bowling Green, Ohio; and hosting an annual working exhibition of restored construction equipment. The next International Convention and Old Equipment Exhibition will be September 23 to 25, 2022, at the National Construction Equipment Museum in Bowling Green, Ohio. Individual annual memberships are $35 within the U.S. HCEA seeks to develop relationships in the equipment manufacturing industry, and offers a college scholarship for engineering and construction management students. Information is available at www.hcea.net, or by calling 419.352.5616, or emailing [email protected].