What comes to mind when you see the word “Ford”? Henry and his mass-produced Model T in the early 20th Century, of course, but how about “F-Series”? That now well-known name originated in the late 1940s, starting with the F1 half-ton pickup and soon extending to F2, F3, and larger models. Ford coined “Super Duty” in the mid-’50s, which described a line of big gasoline V-8s for Big Job medium and heavy trucks. In the late ’80s, SuperDuty (spelled as one word) was applied to a Class 4 cab-chassis model, and soon expanded to include Class 2 through 7 conventional-cab trucks. As for V-8 engines, Henry Ford wasn’t the first to build one, but he and his company did popularize the configuration starting in the early 1930s with their low-priced flathead V-8. Today, modern overhead-valve V-8s comprise the only type of powerplant Ford offers in its SuperDuty F-Series.

The newest example is the 7.3-liter (445-cubic-inch) gasoline V-8 now available in Ford’s SuperDuty heavy pickups. The company’s marketers and engineers announced it last August, and in mid-January made it available to reporters at a ride-and-drive event in the Arizona desert west of Phoenix. There we were treated to an array of F-250, -350 and -450 pickups; although many had the latest Power Stroke diesel, also a V-8, the 7.3 gasser is the one I first sought. It was installed in about a third of the trucks out there and turned out to be so powerful, quiet, and smooth that it’s almost unremarkable to drive. But its newness and basic design make it noteworthy.

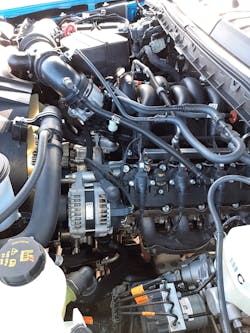

The 7.3, a successor of sorts to the old 460-cubic-inch big-block V-8, is replacing the 6.8-liter Triton V-10 that soon will be out of production. Unlike the single-overhead-cam V-10, the 7.3 V-8 uses traditional pushrods moved by a single in-block cam to actuate rocker arms that open and close the intake and exhaust valves. Pushrod engines run well at lower rpm, which is ideal for commercial-truck applications, according to Patrick Hurtrich, a supervising engineer involved in 7.3 development. The overhead-cam V-10s that I’ve driven needed to rev at 3,000 or higher to make decent power, but the new pushrod V-8’s large displacement allows high power and torque at lower rpm, as I found while driving an F-350 about 50 miles from our hotel to the trailer-towing venue along Arizona 89 at Yarnell. On the level, the engine cruised at 1,700 to 1,800 rpm and seldom revved above 2,000. Then I drove another F-350 hitched to a box trailer weighing 12,000 pounds, and stormed up a 6-percent mountain grade where the engine ran between 2,000 and 2,800 rpm. The truck was capable of towing much more, according to Ford specs. The 7.3 engine is basically quiet, but any noise it might have made was dampened by the vehicle’s highly effective insulation.

The 7.3’s 10.5:1 compression ratio aids fuel efficiency even when running on 87-octane regular gas. In the past, high compression required premium fuel of 92-or-so-octane, but knock sensors allow the 7.3’s electronic ignition to constantly adjust spark and timing. Pushrod engines are also more compact because cylinder heads needn’t house the cams, so the engine easily fits in all Ford trucks, including the heavy pickups, Hurtrich said. The current 6.2-liter gasoline V-8 is standard in most SuperDuty pickups, and the 7.3 will be an option in some SDs and standard in heavier models, including medium-duty F-Series all the way up to the F-750 cab-chassis. For pickups, the 7.3 makes up to 430 horsepower and 475 lb.-ft., enough for many hauling and towing tasks but with a purchase price about $8,000 less than for a 6.7-liter Power Stroke diesel, which is also a pushrod V-8.

For serious loads, Ford’s third-generation Power Stroke is rated at 475 horsepower and 1,050 lb.-ft., which Ford claims are tops in the heavy-duty pickup segment (at least until one of its Big Three competitors leapfrogs ahead). For medium-duty models, the Power Stroke is derated to 330 horsepower and 825 lb.-ft. to better take the stresses of higher loads. The diesel comes with an engine brake that works through the turbocharger to retard downgrade speed of heavy truck-trailer rigs. I can tell you that the engine brake works really well, effectively holding back a 39,000-pound combination I drove with few applications of the service brakes. The combo consisted of an F-450 crewcab dually pulling a 42-foot gooseneck trailer toting a pair of chained-down Kubota machines.

The diesel was mated to a new TorqShift Heavy Duty 10-speed automatic transmission that shifted down to 3rd and 4th gears to make the revs required by the turbo brake at my downward speed of 25 to 35 mph. The engine spun at 3,000 to 3,500 rpm on this steep downhill stretch; uphill, it worked hard but stayed at a pleasingly low 2,000 to 2,200 rpm. The multispeed tranny keeps engine revs at efficient levels, and it shifted strongly and smoothly, though occasionally a tad roughly during downshifts while under load. Most gasoline 7.3s will also be mated to the 10-speed TorqShift (developed, by the way, in a joint venture with General Motors). Manual transmissions are no longer offered, partly because most young people don’t know how to drive them and oldsters would rather not. Also, automatics have become highly efficient and will produce better fuel economy than manuals.

SuperDuty pickups continue with aluminum cabs, hoods, and beds, and high-strength steel underframes. For 2020, a new Tremor package comes with enhanced off-road suspension components but retains full payload and tow ratings, unlike the high-performance Raptor, which trades some hauling capacity for high-speed cross-country travel. The high-slung Tremor comes standard with 35-inch wheels and tires. Besides that and the powertrains, other changes for ’20 are in electronic safety equipment, primarily a Co-Pilot360 package that’s standard on most trim packages. It alerts a driver if the truck is straying from a travel lane, monitors blind spots including those around trailers, and applies the brakes if the driver doesn’t when the truck’s about to hit something up ahead. The latter is part of adaptive cruise control that adjusts speed to suit traffic, something that began appearing in cars and trucks a decade ago. There’s also a Trailer Backing Assist feature that lets a driver “steer” a trailer by twisting a dash-mounted knob that activates the electric-over-hydraulic steering, twisting the wheel left to move the trailer right, etc. I tried it and decided that I could do it just as well by grabbing the bottom of the steering wheel’s rim and moving it the same direction I want the trailer to go—no assist needed, thank you. But I can see that the feature would be helpful to people unfamiliar with trailer backing.

I shan’t say much about the opulence that now surrounds drivers and passengers of modern pickups, including today’s SuperDuties. Ford offers five trim levels, from “rubber-floor” XL to limo-like Limited. XLT, which once was a high-end trim package, is now second to lowest. Every truck I drove had a fancy interior with leather-covered seats, attractive dash and door paneling, and plush carpeting. I believe it would be sacrilegious to drag dirt and mud from a job site into such a cabin, but poshness is what many customers want these days, say reps from Ford and the other builders. Two thousand years hence, archeologists might judge this as a sign of 21st Century America’s high standard of living, kind of like modern scholars explain the gilded chariots of ancient Rome. So, long live style, comfort, and V-8 power.