The mainline slipform paver is the backbone of the concrete-paving industry. These machines are being continually refined for better performance and easier operation, such as this CMI/Terex Series 2000 unit, which features the company's Hydraulic Variable-Width paving system, designed to allow quick changes in paving width.

The transverse-roller paver, or cylinder finisher, such as this GOMACO unit, uses a transversely moving carriage with a hydraulically powered auger to spread concrete in front of a hydraulically powered finishing cylinder, which typically is driven at speeds of 300 to 350 rpm. The machine screeds material to grade on its initial pass, then finishes the surface on its return.

The truss screed, which may span paving widths of 70 feet or more, uses a set of angle blades or square tubes - one leading, one trailing - to screed and finish material. Most provide vibration as well, as does this Metal Forms model, with spinning eccentric weights.

- Mainline slipformer

- Curb & gutter slipformer

- Form-riding paver

- Transverse-roller paver

- Canal/slope paver

- Auger paver

- Roller screed

- Truss screed

- Laser screed

- Who Makes What

- Huron

- Messinger

- M-B-W

- GOMACO

- CMI/Terex

- Power Pavers

- Guntert & Zimmerman

- Somero

- Miller Spreader

- Miller Formless

- Power Curbers

- Allen

- Metal Forms

- Terramite

- Rexcon

- Bid-Well

Whether you're paving an Interstate highway or a driveway, once the transit mixers pull away and leave a sea of expensive, raw concrete that must be quickly transformed into a consolidated mass with a smooth working surface, the proper finishing tools are invaluable. Concrete-finishing tools are the subject of this report, which highlights the types of equipment available for expediently processing raw concrete, then reviews equipment from a diversity of manufacturers.

The mainline slipformer, of course, is the mainstay of street, highway and airport paving. The principal driving force behind the continual technological change in these machines, says CMI's Chapin Sipherd, vice president of concrete applications, is the evermore-stringent demand for improved ride quality. Twenty years ago, he says, an acceptable profilograph reading (using a two-tenths blanking band) may have been 15 inches of accumulated deviation per lane mile. Today, he says, state DOTs typically require readings of 5 inches or less before paying a bonus; DOTs recognize that smooth pavements translate into long-lasting pavements.

The refinement embodied in today's slipformers, especially electronic control, makes these machines the best yet at placing formless pavements that routinely earn ride-quality bonuses. The next technological stride forward, according to some manufacturers, may be the common factory installation of three-dimensional (3-D) local positioning systems as an integral part of the slipformer's control package.

"LPS" technology, essentially, combines the intelligence of a robotic total station, a precision surveying instrument, with a digital model of the paving project to precisely and automatically control the machine's elevation and steering. This technology, potentially, can eliminate expensive, cumbersome grade-control methods (such as string lines) and regulate paving height to a tolerance of ±3 millimeters—less than 1/8 inch.

Among the most versatile of concrete finishing machines are curb-and-gutter slipformers. These machines range from 2,500-pound models that may place curbs at the rate of 50 feet per minute, to 40,000-pound, 150-hp models capable of placing, for instance, both 6-foot-high median barriers along Interstate highways and 16-foot-wide pavements. Like mainline slipformers, these machines have profited from electronic control and have increasingly been refined with operational conveniences, such as easy-to-change molds that offset hydraulically.

The term "form-riding paver" is a bit misleading, because several types of concrete-finishing machines may ride on forms—such as the transverse-roller, auger paver or roller screed. Generally, the term applies to paving machines, which use spreading, consolidating and finishing components akin to those of slipformers, but need forms to contain the material.

Contractors who own form-riders may find them less expensive to mobilize than slipformers on jobs that are of short duration or consist of multiple, isolated paving sites. These machines, although not widely used, are still available and technically competent, such as Allen Engineering's new 12-27-FP, which can pave to 32 feet wide with optional extension kits and features a single-axle transport system.

Also called cylinder finishers, these machines often are used to finish bridge decks, but may find work paving large parking lots, airport aprons, building slabs or streets. The machine's lattice-type mainframe, which is assembled in sections to span the width of the job, supports a transversely moving carriage with a hydraulically powered auger to spread concrete in front of a hydraulically powered finishing cylinder. (Large machines may have dual cylinders.) The cylinder, about 10 inches in diameter, 48 to 60 inches long, and driven at speeds up to 300 rpm, screeds material to grade on its initial pass, then finishes the surface on its return.

These machines move on crawler tracks or on flanged, hydraulically driven traction wheels that ride on pipe rails alongside the slab, or on top of the forms, when used. The cylinder finisher typically advances longitudinally 6 to 12 inches after each cycle, via either operator control or automatically. The cylinder also may vibrate to work up grout in low-slump material, but consolidation is typically handled manually.

According to GOMACO's Carl Carper, vice president of sales and marketing, smaller, trapezoidal-shaped canals can be slipformed with a mold suspended beneath a machine that straddles the opening. If, however, the width of the canal at the top exceeds 40 feet or so, or if depth exceeds 10 or 12 feet, then a modified transverse-roller paver (or "canal paver") typically is used.

For canal-paving applications, the transverse roller's mainframe is modified to take on the shape and dimensions of the structure. Angled "insert sections" connect the bottom mainframe to the side mainframes to yield the proper slope. Some transverse-roller and canal pavers have engines both in the carriage and in the mainframe to power hydraulic functions.

The auger paver is similar in design to a transverse-roller paver, except that the transversely moving carriage has no finishing cylinder. Instead, it has a hydraulically driven auger, a strike off (metering) plow and hydraulic vibrators. It finishes the concrete with surface-vibration blades, which are mounted under the machine's form-riding mainframe. According to Allen Engineering, the auger paver is a lighter-weight, lower-cost alternative to other form-riding machines and finds frequent work at airports.

According to Allen Engineering's Tom Leyes, the roller screed may see action on jobs that contractors consider "hand pours"—small pours where the mainline slipformer may have difficulty maneuvering, or where setting up a large machine is not feasible. Form-riding, single-roller models can pave to widths of 50 feet or more (frame and roller sections slip together to vary width) and can work on slopes, with hydraulically driven traction wheels to propel and steer the machine.

The largest roller screeds have three powered finishing tubes, which may range in diameter, says Leyes, from 6 to 10 inches. The larger the tube, the more concrete the machine can push, thus decreasing material-placement labor and allowing stiffer mixes to be used. In any paving application that uses forms, says Leyes, triple-tube rollers are advantageous. They can pave to widths of 30 feet or more and are ready to work, with no setup, once placed on the forms.

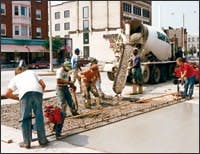

With a lattice-like frame, the truss screed uses a set of angle blades or square tubes—one leading, one trailing—to strike off material, leave a smooth surface, or even a crown. The screed also vibrates, providing a measure of consolidation, via either engine-driven eccentric weights or pneumatic vibration units, supplied from a remote compressor.

These machines are assembled in sections, and heavy-duty models may extend to 70 feet or more. The screed is propelled, usually at 4 to 5 feet per minute, by winching in aircraft-type cables anchored forward of the screed. One-man winch operation and hydraulic winches are options. Says Tom Miller, president of Metal Forms, many concrete contractors own truss screeds for use in situations where space or mobilization costs preclude larger machines, such as airport taxiways and highway interchanges.

Somero Enterprises builds a line of laser screeds, which combine a rubber-tired prime mover with a laser-controlled screed mounted at the tip of a telescopic boom. The model S-240 uses two laser receivers that work in conjunction with an on-board computer to measure screed elevation 10 times per second. The hydraulic, self-leveling screed is 12 feet wide and uses a plow to remove excess concrete, an auger to cut material to grade and a vibration system for consolidation. The laser screed works primarily on commercial-building floors where flatness is critical, but a new 3-D Profiler System is aimed at expanding the machine's application.

SlopeTruss ScreedRoller ScreedAuger PaverLaser ScreedAllenxxxxxxBid-WellxxCMI/TerexxGOMACOxxxxxxGuntert & ZimmermanxxxHuronxxM-B-WxxMessingerxMetal FormsxMiller FormlessxxMiller SpreaderxPower CurbersxxPower PaversxxRexconxSomeroxTerramitex

| Web Resources | ||

| www.allenpavers.com | ||

| www.bid-well.com | www.cmicorp.com | |

| www.gomaco.com | www.guntert.com | |

| www.huronmanufacturing.com | www.mbw.com | |

| www.messingerinc.net | www.metalforms.com | |

| www.millerformless.com | www.millerspreader.com | |

| www.powercurbers.com | www.powerpavers.com | |

| www.rexcon.com | www.somero.com | |

| www.terramite.com/roller_screed.htm | ||