Komatsu's new 100- to 200- hp loaders come with hydrostatic transmissions. A loaded WA250-5 climbed hills 6 percent faster than its predecessor in Construction Equipment Field Tests, and loaded trucks faster at a minimum 29 percent fuel-economy advantage.

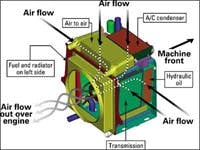

Coolers arranged in a cube around the fan prevent any stacking of the heat exchangers, eliminating some places where debris can get trapped in the Case and New Holland cooling module.

- Average Wheel Loader Costs

- 3-Cubic-Yard Competitors

- Komatsu

- Link-Belt

- Case

- Liebherr

- Daewoo

- New Holland Construction

- John Deere

- Caterpillar

- Volvo

- Hyundai

- Kawasaki

- Dressta

- JCB

- Terex

- Coyote

Category creep has characterized the 100- to 200-hp range of loaders for a long time. The latest round of redesigns continues the trend to higher horse-powers, heavier machines and bigger buckets, but the new emissions-compliant engines have exaggerated the usual productivity gains even while slashing fuel consumption.

Technology leaders among wheel-loader manufacturers have leveraged the benefits of electronic fuel injection¡ªa feature required to meet EPA's Tier II exhaust limits¡ªto upgrade transmissions, hydraulic systems and cooling systems. Some who are particularly motivated to take market share have also been angling for advantages with hydrostatic transmissions and changes in loader design.

Productivity has changed a lot in one generation. Consider Caterpillar's 928. The F Model was rated at 120 horsepower. With its standard 2.4-cubic-yard bucket, it generated 23,874 pounds of breakout force. The 928G comes with 143 horsepower and a 3-cubic-yard bucket. The smallest bucket available on the G, at 2.5 cubic yards, is comparable to the F's standard equipment. With it, the G delivers 16.4 percent more breakout force and weighs just 1,900 pounds more than the F. That kind of metamorphosis has been repeated regularly in this generation of wheel loaders. New models have been hitting the market with improvements in breakout force disproportionate to their increase in horsepower and weight.

It starts with the engine. Engines across this category now come turbocharged, with intercoolers to cool intake air between the turbo and cylinder head. Before the Tier II emissions regs came into effect in January 2003, many wheel loaders under 200 horsepower got by without electronic fuel injection. Meeting the limits made engine computers universal.

Electronic control of fuel systems allows more precise and flexible control of fuel delivery, which increases fuel efficiency and improves horsepower and torque output. Of course, the degree to which different engines deliver each of these benefits varies, but virtually all Tier-II-compliant engines can credibly claim these advantages.

Wheel-loader technology leaders distinguish themselves by how well they integrate electronic fuel injection with controllers on hydraulic systems and transmissions. When the computer controlling fuel injection communicates with computers on the hydraulic system and transmission, each component "knows" how the other components are working. And they can adjust their output to get more out of the machine.

Some manufacturers have exchanged traditional open-center hydraulics for closed-center systems, replacing gear pumps with variable piston pumps like those used in hydraulic excavators. A closed-center hydraulic system relies on a variable-displacement piston pump that can push more or less hydraulic flow into the system in response to changes in system pressure. It improves fuel efficiency because the system isn't constantly pushing oil over relief.

Open-center hydraulics, which are much more common in this wheel-loader category, typically use a fixed-displacement gear pump whose flow only changes in a fixed ratio with engine speed. Excess flow returns to the hydraulic reservoir through a relief valve. Open-center hydraulics tend to use more fuel, but they are simpler and generally less expensive to build and maintain than a closed-center system.

Electronic fuel injection makes closed-center hydraulic systems attractive because the computer controlling the variable piston pump can work together with the engine computer to reach greater levels of power and efficiency. That's why work modes and power-boost options, like those on excavators, are appearing in some wheel loaders.

A more common extension of electronic technology in 100- to 200-hp wheel loaders is the electronically controlled powershift transmission. The transmission's computer senses clutch-engagement pressure, and proportional valves enable precise control of the hydraulic clutches. Clutch pressure is adjusted automatically for smooth shifts in any working conditions. Electronic engine controls have paved the way for highly efficient hydrostatic transmissions, too. Komatsu, Liebherr, Terex and Coyote all offer hydrostatic drives instead of mechanical transmissions. (Two of Terex's five models are hydrostatic.)

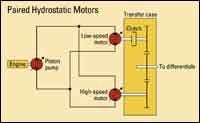

Heavy-duty hydrostats employ a powerful hydraulic pump driven by the engine. The pump supplies two hydraulic motors¡ªtypically one high-speed motor and one low-speed motor. When lots of torque is needed, both drives work through a crankcase. When the machine gets up to speed and torque demand falls off, a clutch removes the low-speed motor from the driveline.

Construction Equipment had the opportunity to Field Test hydrostatic performance by comparing Komatsu's new hydrostatic WA250-5 to the WA250-3 with its powershift gearbox. The Dash-5 machine is a little lighter than the Dash 3, but in truck-loading tests, the new unit's faster cycle times and better bucket-fill factors made it nearly 14 percent more productive than the WA250-3. And the Dash 5 delivered a huge 51 percent fuel-economy advantage. In a 150-foot load-and-carry operation, the Dash 5 outproduced the Dash 3 by 5 percent at a 29 percent advantage in fuel economy.

High-tech engines are bringing maintenance benefits to wheel loaders as well. Most manufacturers enlisted the Tier-II engines' electronics to control a hydraulic fan drive. Separating the fan from the engine for the first time has created a variety of solutions to traditional cooling problems.

Most hydraulic fans are reversible. Either automatically or at the push of a button, the fan can be reversed to blow off debris that has collected on the windward side of the coolers. Manufacturers have been rethinking cooling airflow as they've worked to make room for an intercooler among the radiator, air-conditioner condenser, hydraulic-oil cooler, transmission-oil cooler, and fuel cooler. Case and New Holland, John Deere, JCB, Liebherr, and others have isolated the cooling system in a compartment separate from the engine. Coolers are being repositioned so that they are no longer stacked.

Case, New Holland and Liebherr machines mount their cooling unit between the cab and the engine. In the CNH cooling module, the radiator and all the coolers are arranged in a cubic shape around the fan. None are stacked. The fan pulls air through the coolers and blows it over the engine. The design allowed Case to move the engine rearward, behind the rear axle. Improved counterweighting translated into better breakout forces.

Wheel loaders are the most common high-dollar machines selling. The only equipment categories with larger populations in North America are skid-steer loaders and backhoe-loaders, the sales of which don't deliver nearly as much profit as a wheel loader. It's a profit opportunity that has attracted increased brand competition. New competitors such as Liebherr, Link-Belt and Terex have been trying to cut themselves a piece of wheel-loader pie.

As mentioned, Liebherr and Terex are working to distinguish their products with hydrostatic transmissions. Link-Belt and Terex offer a twist on the usual Z-bar front-end linkage that resembles the Volvo arrangement. It's a Z-bar, but reverses the traditional connections. The hydraulic cylinder attaches to the bottom of the bar, and the link to the bucket connects to the top. The makers claim the geometry delivers more breakout force to the machine's full lift height than the common Z-bar. And Link-Belt says that its fork-leveling sensors automatically regulate the position of the lift and curl cylinders to keep the load level through the lifting cycle.

Tier II engines have no doubt consumed much of recent research-and-development resources for 100- to 200-hp loaders. But there is ample variation in hydraulic systems, transmissions, cooling systems, and front-end linkages to make today's wheel-loader offerings more than just an engine competition.

| Web Resources | ||

| Case www.casece.com |

||

| Caterpillar www.cat.com |

Coyote www.coyoteloaders.com |

|

| Daewoo www.dhiac.com |

Dressta www.dresstanorthamerica.com |

|

| Hyundai www.hceusa.com |

Intensus www.intensus.com |

|

| JCB www.jcbna.com |

John Deere www.deere.com |

|

| Kawasaki www.kawasakiloaders.com |

Komatsu www.komatsuamerica.com |

|

| Link Belt www.lbxco.com |

Liebherr www.liebherr.com |

|

| New Holland www.newhollandconstruction.com |

TCM www.tcmglobal.net |

|

| Terex www.terexamericas.com |

Volvo www.volvoce.com |

|