Few machines have gained popularity in such a relatively short time as has the compact track loader (CTL). Compared with its main competitor, the skid steer loader, industry statistics indicate that less than a decade ago, the sales mix between skid steers and CTLs was divided about 60/40 in favor of the skid steer. By 2017, those percentages had reversed, and the CTL seems still to be gaining ground.

The appeal of the CTL resides largely in its undercarriage, which uses rubber tracks that give the CTL a flat-footed stance that numbers among its advantages reduced ground pressure, greater lifting capacity, added stability for attachment handling, smoother ride, and the ability to work in more adverse ground conditions.

Although the skid steer (SSL) and the CTL do share certain fundamental design features, CTL manufacturers generally have not simply adapted existing SSL models to accept a crawler undercarriage. Instead, most manufacturers have approached the overall design of the CTL as an independent model—with features that enhance performance with a track undercarriage.

To best capitalize on the inherent performance characteristics built into the CTL’s rubber-track undercarriage, good operating and maintenance practices should be priorities—which also might yield the added benefit of extended useful life for the tracks. Good practices coupled with a knowledgeable replacement plan can help ensure optimum value from the track investment.

CTL undercarriages can be classified into two general groups, perhaps best identified by the type of sprockets used; for convenience, call the two groups “external-drive” and “internal-drive.” (Internal-drive type undercarriages also are called ASV undercarriages; this type was developed by ASV for its Posi-Track loaders and is used today on its range of track models, as well as on Caterpillar Multi-Terrain loaders.)

The external-drive undercarriage uses steel drive sprockets similar to those used on crawler dozers. The sprocket teeth transfer power from the hydrostatic drive motors to the tracks by pushing against transverse steel lugs embedded in the rubber. By contrast, the internal-drive undercarriage uses a cylindrically shaped sprocket that has transversely positioned rotating steel sleeves that push against rubber lugs on the inside of the track.

The overall design of the typical external-drive CTL undercarriage uses an elevated sprocket and a large central frame that houses a number of steel rollers along the bottom and large steel idlers front and rear. The embedded steel lugs provide a running surface for the bottom rollers, and the track is guided under the rollers by vertical tabs on the embedded lugs.

The internal-drive undercarriage has a substantially different design. Specifics vary somewhat depending on machine size, but a typical configuration might consist of a relatively small track frame mounted to the tractor frame with a pair of torsion axles that provide suspension. Mounted to the track frame are four pairs of rubber-clad wheels that ride directly on the inside of the track. Also mounted to the track frame, front and rear, is a pair of larger, rubber-clad idler wheels. The track is kept centered as it runs beneath the wheel pairs by the rubber sprocket-drive lugs, which run down the center of the track.

CTL track and tread design

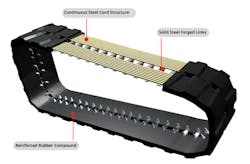

The design of the track itself also differs significantly between the two undercarriage types. The external-drive track, in addition to the transverse steel lugs, also contains a series of steel cords or cables.

“The cables and the steel lugs are separated by a layer of rubber,” says Dan Wintemute, operations manager at DuroForce, a company that manufacturers both types of tracks. “The steel lugs vibrate and shift slightly inside the rubber track. If the lugs were contacting the cables, this movement would lead to wear and possible damage.

“Earlier track designs were manufactured with joined cables, meaning that the individual cables are looped around the track once, then the ends joined together by welding, crimping, or other methods,” says Wintemute. “Later designs use a continuous cord, meaning that one long cable is wrapped around the track over and over again—think of wrapping a piece of string around your finger multiple times. This is done on both sides of the track and creates a stronger assembly, because there are no joints to pull apart or break.”

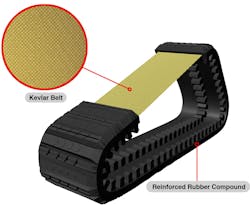

According to Buck Storlie, product line manager, ASV Holdings Inc., tracks used on the internal-drive undercarriage contain no embedded steel.

“A key feature of the ASV track is the lack of steel, which would add weight and negate the purpose of the overall design,” says Storlie. “Instead of using steel to strengthen the track, ASV tracks use a belt of synthetic fiber, generally called an aramid fiber, which is heat-resistant and extremely strong. This design results in a track that provides optimum flexibility and traction.”

Another factor of track design is rubber compound and tread pattern. Equipment managers basically have no say in the compound used, but they do usually have a choice of tread patterns. The equipment manufacturer and dealer or track supplier can assist in this regard, and tread choices typically are dictated by the type of work the machine primarily does.

“Camso offers multiple tread patterns across different quality lines for CTLs,” says Andrew Gaffney, product line manager at Camso, now part of the Michelin Group. “For example, the SD line is better suited for soft surfaces where more traction is required, and the HXD line for increased abrasion resistance in more intense applications. Different tread patterns are available for both lines.”

For CTLs, the machine manufacturer usually has a preference for the tread pattern used.

“For Caterpillar CTLs, tread patterns are either block or bar,” says Kevin Coleman, product specialist. “The block type uses large trapezoidal pads, which give good performance in a range of applications. The other choice, bar style, uses a transverse bar having a tapered edge that helps control ground disturbance during turns. The bar style also works well in snow-removal applications.”

The style of track-tread patterns available varies with the manufacturer and supplier, says Gregg Zupancic, product manager, John Deere Construction.

“The first track-tread option offered by John Deere is the ‘zig-zag’ pattern,” says Zupancic. “This pattern bites into the soil to provide more traction when pushing material, and it’s most efficient for passing over the rolling components of the undercarriage. A downside to this pattern, however, is reduced capabilities while working perpendicular to a slope. The second option is the ‘block-lug.’ The staggered lugs in this pattern tend to be more durable and are able to handle rougher applications and terrain with debris and rocks.”

CTL operating style and hazards

“The most significant impact on track life is operation and application,” says Zupancic.

The operator usually has no control over the CTL’s application, but definitely has a say in how the machine is run. The rules for good operation and for avoiding hazards are relatively few—but important to practice.

“Spinning the machine in 180- or 360-degree movements will wear the tracks more rapidly than making ‘V’ or three-point turns,” says Caterpillar’s Coleman. “There are times when the operator has to spin the machine in the circle in which it’s positioned, and that’s fine, but don’t do it when the maneuver is not really needed.”

“The operator can also extend track life by turning on softer ground before approaching a harder surface,” says Zupancic.

“Spinning the tracks into the ground when making rapid directional changes is a bad habit that increases track wear,” says DuroForce’s Wintemute. “Operators also need to be mindful of their surroundings; running over and pushing through debris when it can be avoided can rip apart a track and render it useless.”

“Anything that damages the edge of the track is to be avoided whenever possible,” says Coleman, “such as running up against a curb or running against a retaining wall.”

To that caution, Wintemute adds that continually bumping the track against a curb or retaining wall can damage the steel in the track. Hitting the front of the track against a hard surface forces the steel lugs into the front idler and can eventually fracture the lug.

Camso’s Gaffney gives a final caution.

“We’ve seen instances of steel cable breakage when an operator accelerates quickly to get out of the mud.”

As with rules for good operating practices, rules for good maintenance are few, but, again, critical for acceptable track life.

“Proper track tension is all-important,” says Zupancic. “John Deere recommends checking track tension on our products every week or every 50 hours of operation. If tension is too tight, it can rob horsepower, prematurely stretch the track, and create heat that can permanently damage the rubber. If the tension is too loose, you risk the track coming off and damaging the rubber, the steel embeds, and undercarriage components.”

A few CTL models have a self-tensioning feature, but most do not. The operator’s manual is the best source for information about how to measure and adjust track tension. Adjusting tension usually is accomplished by adding or relieving grease from the recoil mechanism. Internal-drive undercarriages use a turnbuckle arrangement for tension adjustment.

“Undercarriage cleanliness is a key item for extending track life,” says Gaffney. “Dried mud and clay or frozen snow and ice need to be removed. Another important element to monitor are the sprockets. Look for the appearance of a ‘shark-fin’ profile of the teeth—thinning and sharpening of the teeth at the wear tips, a condition that can damage track rubber. It’s good practice to set up regular undercarriage inspections with the equipment dealer.”

ASV’s Storlie notes also that the sprocket in internal-drive undercarriages should be inspected for wear of the outer roller sleeves, inner pins, and support rings. The roller-sleeve assemblies in these sprockets can be rebuilt.

CTL track replacement

The optimum time to replace tracks seems less a science than a studied judgment call.

“Machine owners should keep in mind that a track can fail before the tread wears out,” says Gaffney. “An increasing amount of exposed cable is an indicator that track replacement might be required.”

“Visual tears and punctures in the track rubber are two main indicators that tracks might need to be replaced,” says Zupancic. “Another indicator is increased machine vibration, a sign that the inside of the track is wearing out. Also, be aware of increased noise, the possible result of the steel lugs no longer having enough rubber to buffer them against the steel in the running undercarriage components.”

For internal-drive undercarriages, says ASV’s Storlie, improper track tension can cause the rubber drive lugs to wear and necessitate track replacement.

“When the tracks are replaced,” says Caterpillar’s Coleman, “carefully inspect all undercarriage components, for example, looking for oil leaks that could indicate failing seals in rolling components. In many instances, machine owners replace sprockets with the new tracks.”

DuroForce’s Wintemute offers this cautionary advice:

“If your machine is a vital part of your business, you might want to replace the tracks when the tread reaches about 20 percent of its original depth. It might seem foolish to replace a track that is still operable, but in most case, the overall cost of replacing a broken track exceeds the cost of doing an early replacement in a repair facility, not in the mud of the job site, and on your time schedule, not in the middle of a project.”